What Happens To Brain Function As We Age

14 min read Explore how brain function changes with age, including cognitive decline, neuroplasticity, and actionable tips for maintaining cognitive health in later years. (0 Reviews)

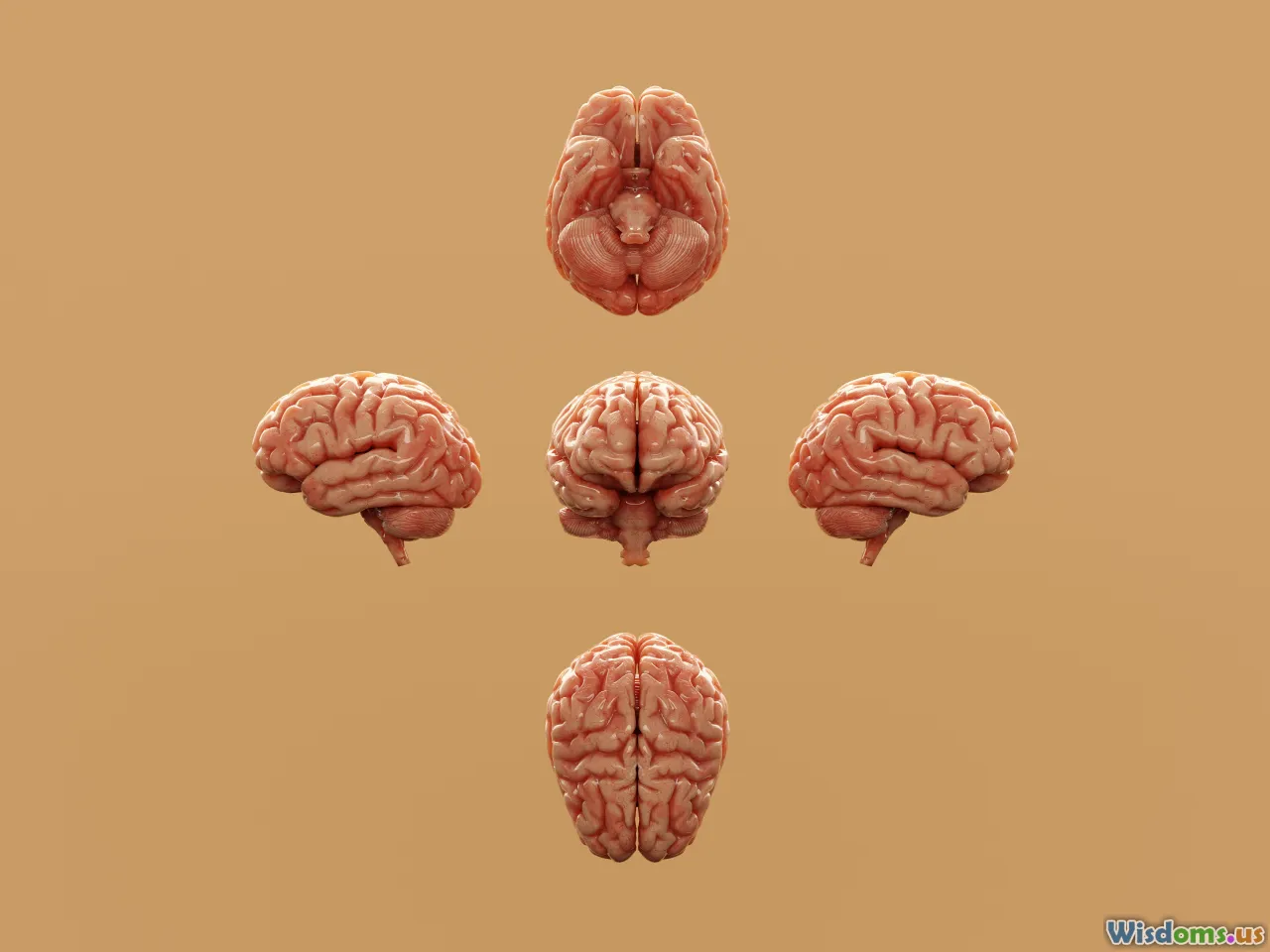

What Happens to Brain Function as We Age

Aging is a journey we all take, and nowhere are its effects more intriguing—and sometimes concerning—than in how it touches our brains. Contrary to popular belief, cognitive decline is not inevitable; our brains demonstrate both vulnerability and remarkable resilience as the years pass. In this article, we explore the complex landscape of brain function over time, separating fact from fiction, and sharing steps to keep your mind vitally sharp.

The Structure and Function of the Aging Brain

One of the first changes seen with aging occurs at the micro-level: the neurons and connections that form the foundation of our brain’s cellular network. Grey matter, which contains most of the brain’s neuronal cell bodies, tends to diminish slowly from middle age onward. This decrease doesn’t necessarily equate to dramatic loss; many neurons remain quite robust.

At the same time, white matter—the tissue responsible for linking different brain regions—can thin due to myelin breakdown, hampering communication between brain areas. For example, the prefrontal cortex, which governs executive functions and decision-making, is among the most susceptible to age-related shrinkage. In contrast, areas linked to basic functions like movement and sensation are less dramatically impacted.

Changes in neurotransmitters such as dopamine (linked with pleasure, motivation, and attention), serotonin (regulator of mood and sleep), and acetylcholine (important for memory and learning) further illustrate the natural wear and tear. A real-world case is Parkinson’s disease, often developing with age-related dopamine decline, underlining how neurochemistry and brain structure together shape function.

Common Cognitive Changes: What's Typical, What's Not

Everyone forgets a name or misplaces keys at times, but how can you tell what’s normal versus a warning sign? While some cognitive slowing is to be expected, major interruptions to daily life are not a normal part of aging.

Typical age-related changes may include:

- Slower processing speed

- Occasional memory lapses (e.g., forgetting appointments briefly but recalling them later)

- Greater difficulty multitasking

Atypical or concerning signs (possibly pointing to conditions like mild cognitive impairment or dementia) might feature:

- Consistently forgetting important information

- Trouble following simple conversations

- Getting lost in familiar places

For instance, a multi-country study published in Neurology (2019) confirms that while brain volume and memory scores tend to decline gradually past age 60, the majority of older adults continue to live actively and independently without severe impairment.

Plasticity: The Brain's Hidden Power at Any Age

The notion that "you can’t teach an old dog new tricks" is outdated—thanks to neuroplasticity. Even into our 70s, 80s, and beyond, the brain remains surprisingly adaptable. Plasticity lets us learn new skills, create memories, and even reroute functions in response to injury or illness.

Recent brain imaging studies—such as those done at Harvard’s Center for Brain Science—have shown that adults who take up challenging new hobbies (for instance, learning a new language or instrument) actually build new neural pathways and boost cognitive reserve. This reserve can help compensate for normal declines and may even delay the onset of dementia-related symptoms.

Research from the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) trial highlights that training specific skills (like reasoning or memory tasks) in older adults leads to measurable, lasting improvements. In other words, mental workouts matter as much as physical ones.

Age, Memory, and Learning: What Changes?

Memory often stands at the forefront of concerns about brain aging. But memory is not a single process—it comes in many forms:

- Short-term (working) memory: Our ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information. This may become less efficient.

- Episodic memory: Remembering life events declines mildly with age—like recalling details of last year’s vacation.

- Semantic memory: Knowledge of facts, meanings, and concepts usually stays stable or even improves.

- Procedural memory: Skills like riding a bike or playing an instrument are least affected.

For example: Studies at the Mayo Clinic reveal older adults frequently excel in vocabulary tests (semantic memory), while younger adults outperform in tests of memorizing lists or rapidly learning novel information (episodic memory).

Strategies like writing reminders, using calendars, and practice through repetition can mitigate many challenges. Notably, "spaced repetition"—spreading out learning over time—benefits older learners much as it does the young.

The Impact of Lifestyle Choices on Brain Health

How we live each day deeply shapes our brain trajectory. Consider some key influencers:

-

Physical activity: Regular aerobic exercise stimulates neurogenesis (the creation of new neurons) and enhances blood flow, which benefits learning and memory. A University of Illinois meta-analysis found walking three times per week for six months improved hippocampal volume (crucial to memory) in seniors.

-

Nutrition: Diets rich in leafy greens, fatty fish, nuts, and berries—often collectively known as the Mediterranean or MIND diets—supply antioxidants and omega-3s that support cognitive function. An illustrative 2015 study in Alzheimer’s & Dementia reported that participants on a MIND diet had brain-aging rates equivalent to being 7.5 years younger.

-

Social engagement: Loneliness can be as damaging as smoking 15 cigarettes a day, according to research highlighted by the UK’s Campaign to End Loneliness. Genuine connections foster cognitive resilience and stave off decline.

-

Sleep: Consistent, quality sleep is fundamental. During deep sleep, the brain consolidates memories and flushes away metabolic waste. Chronic sleep deprivation, by contrast, raises risk for long-term cognitive impairment.

-

Mental stimulation: Novelty and curiosity matter—reading, playing chess, or engaging in debates all count. The longitudinal Nun Study famously found that nuns maintaining mental and social engagement into advanced age had lower rates of dementia, emphasizing the protective power of lifelong learning.

Age and Emotional Regulation: Growing Wiser with Time?

Contrary to stereotypes that depict old age as a period of decline, many studies find that emotional regulation improves with time. Older adults, on average, are better at focusing on positive information and are more resilient in the face of setbacks.

For example, Laura Carstensen’s Stanford research into the “positivity effect” reveals that older adults filter out negative stimuli and emphasize emotionally meaningful experiences. This contributes to overall increased subjective well-being—often despite physical or cognitive setbacks.

Mindfulness practices, journaling, or gratitude reflection can amplify this natural bias toward positivity, giving older adults a toolset to further improve emotional resilience.

Neurodegenerative Disease Risk: What’s Preventable?

The risk for conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and vascular dementia rises with age, but the causes are complex and often modifiable. Genetic factors do play a role—but lifestyle exerts a powerful influence.

For instance, a landmark 2020 Lancet commission review concluded that up to 40% of dementia cases globally could be delayed or prevented by managing 12 key risk factors, including hypertension, obesity, hearing loss, depression, diabetes, inactivity, and smoking.

Practically, addressing hearing loss (with aids or therapy) can significantly protect cognitive health, as social isolation and reduced mental stimulation are mitigated. Blood pressure management, diabetes control, and following care for cardiovascular health further contribute to reduced neurodegenerative risk.

On the pharmaceutical frontier, drugs that target amyloid plaques, tau proteins, or disruption of neuroinflammation represent intense areas of research, though preventive lifestyle choices remain the surest bet for now.

Tips and Actionable Steps for Maintaining Brain Health

Harnessing the power of scientific insight, you can stack the deck in your favor. Here’s a roadmap for supporting lifelong brain health:

1. Move daily: Even a brisk 20-minute walk provides cardiovascular—and cognitive—dividends.

2. Eat mindfully: Prioritize bright vegetables, omega-3 fats (such as salmon or flaxseed), nuts, berries, and limit processed foods.

3. Stay social: Join clubs, volunteer, or connect regularly with friends or neighbors. If in-person interaction isn’t possible, phone or video chats count, too.

4. Challenge your mind: Mix in variety: puzzles, foreign language lessons, artistic pursuits. Rotate activities to stimulate different brain regions.

5. Establish routines: Keep a regular sleep schedule. Sleep hygiene techniques—avoiding blue light pre-bed, keeping consistent bed and wake times—are crucial.

6. Manage health risks: Track blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, and address hearing loss or depression proactively with professional guidance.

7. Seek novelty: Even small changes—trying a new recipe, exploring a new route on your walk—can keep your brain adaptable.

The Power of Purpose and Lifelong Learning

Finally, research is increasingly clear: Living with purpose, curiosity, and a continuing sense of discovery yields real dividends for brain aging. People who engage in meaningful activities—volunteering, mentoring, creative expression, or spiritual pursuits—tend to enjoy slower rates of decline and greater life satisfaction.

Dr. Patricia Boyle’s work at the Rush Memory and Aging Project found that seniors with high purpose-in-life scores were significantly less likely to develop Alzheimer’s, even when other risk factors were present. Purpose can be as simple as caring for a plant, learning to paint, or participating in intergenerational projects.

When we understand that aging is not just about staving off loss, but about continually finding ways to grow and contribute, our brains receive bountiful benefits—in structure, function, resilience, and joy.

Embrace the changes, nurture your curiosity, and treat your brain to a lifetime of engagement. The path of aging may be inevitable, but how you travel it—and how vibrant your mind remains—is a journey you can help design.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts