Why Your Brain Sometimes Makes Irrational Choices

10 min read Explore why our brains often choose irrationally despite our desire for logic and control. (0 Reviews)

Why Your Brain Sometimes Makes Irrational Choices

Have you ever caught yourself making a decision that, in hindsight, makes no logical sense? Perhaps you hesitated to invest in a stable opportunity or splurged on a luxury item despite knowing your budget constraints. It turns out that such irrational choices are not merely around our lack of discipline—they’re deeply rooted in how our brain functions. Understanding why our brain sometimes makes irrational choices is crucial not only for personal growth but also for improving decision-making in business, relationships, and everyday life.

The Architecture of Decision-Making: Rational vs. Irrational

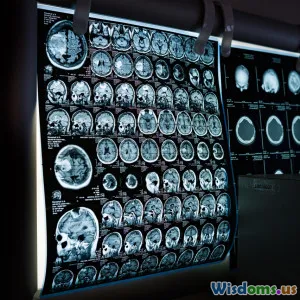

Before diving into why irrational decisions occur, it helps to briefly understand what happens in our brain during decision-making. Our brain is a complex organ wired for both logic and emotion, often balancing conflicting impulses.

Dual-Process Theory: System 1 and System 2

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman popularized the Dual-Process model to explain our decision-making processes:

- System 1 operates fast, automatically, and often subconsciously. It is governed by heuristics and intuition — quick judgments based on previous experiences.

- System 2 is slow, deliberate, and conscious. It allows for analytical thinking, weighing pros and cons.

Irrational choices often emerge when System 1 dominates, offering swift but imperfect shortcuts at the expense of logical analysis.

Why the Brain Trips: Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking, influencing our perception and judgment. These biases shape irrational behavior consistently across individuals.

Anchoring Bias

This occurs when individuals rely heavily on the first piece of information they encounter — the “anchor” — when making decisions. For instance, if the initial price you see for a car is $30,000, you might consider a discounted price of $27,000 a good deal, even if the actual value should be much lower. The brain clings to anchors because it conserves energy by simplifying complex evaluations.

Confirmation Bias

Our tendency to seek and prioritize information that confirms existing beliefs fuels irrational choices. A famous study demonstrated this with political opinions: participants favored news articles supporting their views and ignored contradicting evidence, perpetuating blind spots.

Loss Aversion

Behavioral economists have observed that people dislike losses more than they enjoy equivalent gains—a principle called loss aversion. This bias can lead us to irrational decisions like holding onto losing stocks or avoiding risks that are statistically favorable, rooted in the brain’s evolutionary need to avoid danger.

Availability Heuristic

When making decisions, we often rely on information that is most readily available, like recent news or vivid memories—even if it's unrepresentative. For example, people may irrationally fear plane crashes more than car accidents because the former receive more media attention, despite being rarer.

Emotional Interference: When Feelings Override Facts

Our emotions profoundly shape decision-making, frequently overriding rational analysis.

The Role of the Amygdala

The amygdala governs emotional responses such as fear and pleasure. In threatening or high-pressure situations, amygdala activation can hijack judgment. Neuroscientific research using fMRI scans has shown that people are likely to make risk-averse choices when the amygdala is more active, evidencing snap emotional interference.

Emotional Decision-Making Examples

Consider buying lottery tickets. Logically, the odds are dismal, but the excitement of potential win activates reward circuits, compelling many toward irrational spending.

Similarly, in relationships, emotions can cloud judgment—leading to impulsive decisions like staying in harmful situations or rushing into commitment.

Evolutionary Perspectives: The Brain’s Survival Instincts

Our brain’s architecture is also a product of natural selection. What appears irrational today might have been adaptive for survival in prehistoric environments.

Quick Decisions Enhance Survival

Our ancestors had to make split-second decisions — choosing fight or flight over pondering pros and cons. Fast, heuristic thinking often favored survival but can be counterproductive in modern complex contexts requiring extended deliberation.

Fear of the Unknown

Evolution wired us to distrust ambiguity because unknown threats posed danger in ancestral environments. This tendency sometimes manifests as irrational fear of new experiences or resistance to change, despite potential benefits.

Neurochemical Influences: Brain Chemicals That Affect Choices

Neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin play key roles in decision-making, especially in relation to reward and mood.

Dopamine and Reward Prediction Error

Dopamine release reinforces behavior expecting reward. Sometimes, misfiring or hypersensitivity to dopamine can lead to risk-taking or addictive behaviors. For example, research on gambling addiction ties excessive dopamine activity to chasing losses despite poor odds.

Serotonin and Impulse Control

Low serotonin levels have been linked to impulsivity and poor decision control, explaining why individuals might make rash choices when under stress or emotional distress.

Real-World Case Studies: Irrational Brain at Work

To illustrate these concepts, let’s look at some examples where irrational choices have tangible effects.

Financial Decisions and the 2008 Crash

Many experts argue that cognitive biases and emotional decision-making fueled risky behaviors leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. For example, overconfidence bias made investors believe housing prices would keep rising, ignoring mounting data warning of a bubble.

Healthcare Decisions

Patients often make irrational health choices due to fear or misinformation—the vaccine hesitancy phenomenon models confirmation bias and emotional processing overtaking scientific facts.

Consumer Marketing Influence

Marketers exploit heuristics and biases—using scarcity (limited-time offers) to trigger purchase urgency or anchoring by showing high original prices to heighten perceived discounts.

Strategies to Mitigate Irrational Choices

Awareness is the critical first step to curb irrational decisions.

Practice Metacognition

Reflecting on your own thought processes can activate System 2, questioning immediate intuitions and biases.

Gather Diverse Information

Broaden your sources to combat confirmation bias. Chatting with people who challenge your views or reviewing opposing data deepens insight.

Emotional Regulation Techniques

Mindfulness and stress-reduction methods reduce amygdala hijacks.

Use Structured Decision Tools

Techniques such as decision trees, pros and cons lists, or consulting experts can add rigor and reduce heuristic reliance.

Conclusion: Embracing the Brain’s Complex Nature

Your brain’s occasional irrationality is not a flaw but a reflection of its evolutionary brilliance and biological complexity. By understanding the cognitive biases, emotional forces, and neural mechanisms behind irrational choices, you gain the power to recognize and manage them consciously.

True mastery lies not in eliminating irrationality—impractical given brain architecture—but in learning to harness both intuition and reason, matching the right tool to each decision context. Next time your brain nudges you toward an impulsive or illogical choice, pause and consider the hidden wiring beneath. With insight and practice, irrational decisions can transform from frustrating pitfalls into opportunities for growth and wiser living.

References:

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 10(3), 295-307.

- Loewenstein, G., & Lerner, J. S. (2003). The role of affect in decision making. Handbook of affective sciences, 619, 642.

- Phelps, E. A. (2006). Emotion and cognition: Insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 27-53.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts