Asia Versus Europe Education Systems A Data Driven Comparison

10 min read An in-depth data-driven comparison of education systems in Asia and Europe revealing key differences and insights. (0 Reviews)

Asia Versus Europe Education Systems: A Data-Driven Comparison

Education forms the backbone of societal progress, influencing economic growth, innovation, and social well-being. Across the globe, Asia and Europe represent two vast, culturally diverse regions with distinct education systems shaped by history, values, and government priorities. This article dives deeply into a data-driven comparison between these two continents’ education systems, shedding light on how various factors interplay to influence learning outcomes. From curriculum design to student achievement, we explore what makes each system unique and how lessons from each might serve to improve global education.

Understanding the Foundation: Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate the differences between Asian and European education systems, it’s crucial to recognize their historical and cultural backgrounds.

Asia’s Education Ethos

Asian education largely reflects Confucian values emphasizing respect for authority, diligence, discipline, and collective success. Countries like South Korea, Japan, China, and Singapore have long histories of rigorous academic focus, where education is seen as a primary avenue for upward mobility.

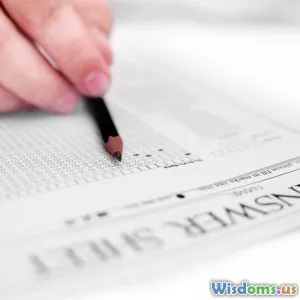

For instance, the use of rote memorization and extensive examination systems, such as South Korea’s notoriously competitive “Suneung” university entrance exam, reveal the continent’s emphasis on standardized academic achievement. According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018 data, several Asian countries rank in the top 10 globally for mathematics, science, and reading proficiency, underlining the effectiveness of their rigorous schooling.

Europe’s Educational Tradition

Europe’s education legacy is rooted in a blend of the Enlightenment’s emphasis on critical thinking and humanism, alongside diverse national values across countries. Countries like Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands prioritize student well-being, creativity, and balance. The Finnish education system, for example, is globally famous for its minimal homework policies, highly trained teachers, and low-stakes testing, placing less stress on standardized exams.

Further, Europe’s diverse cultural landscape has resulted in comprehensive education systems that emphasize equality and holistic development that extends beyond academics, incorporating arts, physical education, and civic learning.

Curriculum and Pedagogical Approaches

Asia: Standardization and Discipline

Asian education tends to be centralized with highly structured national curricula. For example, China’s Ministry of Education prescribes detailed curricula nationwide, ensuring adherence to rigorous academic standards.

This system prioritizes core subjects like mathematics, science, and language proficiency, often at the expense of extracurricular activities. The consequence is a high degree of uniformity and comparability in student performance across regions.

Pedagogically, many Asian classrooms utilize teacher-centered methods focusing on direct instruction, extensive practice, and exam preparation. A 2019 report by the OECD indicated that Asian students often spend 30% more hours per week studying outside of school compared to European counterparts.

Europe: Flexibility and Student-Centeredness

European countries tend to offer more flexibility in curricula, encouraging creative problem solving and student autonomy. For example, Germany’s dual education model combines vocational training with academic education, supporting diverse learner pathways.

In Nordic countries like Finland, the curriculum is broad and balanced, emphasizing interdisciplinary learning and social skills alongside academics.

Pedagogically, European systems encourage interactive learning, collaboration, and formative assessments to support continuous progress. According to EU’s Eurydice report, student-led projects and experiential learning are increasingly prevalent in European classrooms.

Student Performance and Assessment

Insights from PISA Rankings

PISA tests, administered every three years to 15-year-olds globally, provide a standard yardstick to compare education outcomes.

-

In the 2018 PISA results, Asian countries dominate top spots with Singapore ranking 1st, China’s provinces (Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang) within top 5, and South Korea ranking 7th. These countries excel particularly in mathematics and science.

-

European leaders like Finland (12th), Estonia (7th), and the Netherlands (13th) perform well, but generally lag behind their Asian counterparts in raw scores, especially in math.

Importance of Holistic Learning Indicators

However, academic tests do not provide a complete picture. The World Happiness Report and other studies indicate that European students often report higher well-being and lower stress levels than many Asian students.

For example, a recent study by the OECD showed that stress levels among South Korean and Japanese students were among the highest worldwide, correlating with longer study hours and competitive pressures.

This underscores a critical contrast: Asian systems achieve top academic results mainly through intensity and repetition, while European systems aim for equilibrium between performance and mental health.

Teacher Education and Professional Development

Asia’s Emphasis on Content Mastery

In countries like Japan and Singapore, teacher training is highly selective and content-driven. For example, Singapore’s National Institute of Education requires rigorous training, and teachers undergo continuous professional development to maintain high standards.

Teachers in many Asian countries also enjoy a prestigious social status, and their work hours extend beyond classroom teaching to coaching and exam preparation.

Europe’s Focus on Pedagogy and Autonomy

European nations often emphasize pedagogical skills, classroom management, and adaptability. Finnish teachers must hold master’s degrees and receive heavy training in research-based methodologies.

Moreover, European teachers generally have more autonomy to tailor their instruction to student needs. Studies show this autonomy correlates positively with job satisfaction and teaching effectiveness.

Government Investment and Policy Effects

Funding Models

Asian countries typically invest heavily in standardized testing infrastructure and supplementary tutoring sectors. For instance, South Korea’s private tutoring market is one of the biggest globally, reflecting the cultural prioritization on academic excellence.

In contrast, many European nations allocate funding to support inclusive education, early childhood development, and student support services—programs that address equity and broaden access.

Policy Innovations

Singapore’s education reforms focus on lifelong learning, infusing technology, and adapting curricula to future skills. Meanwhile, Finland invests extensively in early childhood education and reduced homework policies to foster holistic growth.

Such dynamic policies highlight the adaptive nature of educational governance.

Lessons and Future Directions

Asia’s education strengths lie in consistency, discipline, and strong academic outcomes, yet they grapple with student stress and creativity constraints. Europe offers balanced education promoting innovation and well-being but may face challenges in reaching uniformly high academic standards.

Hybrid models blending Asian rigor with European flexibility may provide innovative ways forward. Countries could benefit from:

- Incorporating well-being measures within intense academic environments.

- Expanding vocational training to diversify student pathways.

- Leveraging technology to personalize learning.

As globalized economies demand versatile skill sets, education systems must evolve to nurture both knowledge mastery and creativity.

Conclusion

The education systems of Asia and Europe reveal fascinating contrasts and strengths shaped by contrasting cultures, histories, and policymaking frameworks. Data confirms Asia’s impressive academic achievements while highlighting Europe’s focus on holistic development and student welfare.

Understanding these differences is more than an academic exercise—it’s a vital step toward fostering globally competitive yet humane education practices. Policymakers, educators, and learners alike stand to gain from a cross-continental dialogue informed by robust data and thoughtfulness, aiming for education systems that serve all dimensions of human potential.

Whether one prioritizes high test scores or student happiness, the perfect system perhaps lies in embracing the best of both worlds with evidence-based innovations and continuous learning.

References

- OECD PISA 2018 Results: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/

- Eurydice European Education Report, 2018

- World Happiness Report, Student Wellbeing Edition, 2020

- Singapore Ministry of Education, Teacher Training Overview

- Finnish National Agency for Education, Curriculum Framework

- South Korea Education Statistical Yearbook, 2021

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts