Can Restorative Justice Replace Traditional Punishments

15 min read Examining whether restorative justice can effectively replace traditional punitive systems in addressing crime and conflict. (0 Reviews)

Can Restorative Justice Replace Traditional Punishments?

The landscape of criminal justice is shifting. Rather than relying solely on punitive measures, policymakers and practitioners worldwide are now exploring approaches that focus on healing, accountability, and rebuilding communities. At the heart of this evolution is restorative justice—an alternative framework that seeks not just to punish, but to restore. But can restorative justice truly replace traditional punishments? To answer this, we must delve beyond surface comparisons and assess the potential, principles, and real-world outcomes of both systems.

Understanding the Foundations of Restorative Justice

Restorative justice is rooted in the belief that crime is not just a violation of law, but a wound in human relationships. This approach seeks to bring together those harmed (victims), those responsible for harm (offenders), and relevant community members in a collaborative process. Its goals: understanding, accountability, repairing harm, and building path forwards.

Core Principles

- Voluntary Participation: In most restorative initiatives, participation by all parties is voluntary, a crucial difference from the coercive nature of many legal punishments.

- Direct Dialogue: Restorative processes typically encourage direct and safe communication among those involved, fostering empathy and accountability that traditional courts rarely achieve.

- Repair Over Retribution: The focus shifts from 'what law was broken?' to 'who was hurt?' and 'what needs to be repaired?'.

Examples of restorative practices include victim-offender mediation, family group conferences, and peace circles. For instance, a 12-year-old who vandalized a community center may meet the affected staff, accept responsibility, hear the impact, and contribute to repairing the damage—often leading to more meaningful change than court-imposed community service.

Traditional Punishments: A Critical Overview

Traditional punishment systems are shaped by the concepts of deterrence, retribution, incapacitation, and rehabilitation. Through fines, incarceration, probation, or community service, the state imposes legal consequences intended to dissuade wrongdoing.

Problems and Limitations

- Recidivism: Studies consistently show high rates of recidivism among those exiting prison. In the United States, about 68% of released prisoners are rearrested within three years (source: Bureau of Justice Statistics).

- Victim Exclusion: Conventional procedures often minimize the voice and needs of the actual victim, focusing more on lawbreaking than on harm done.

- Collateral Harm: Besides the individual punished, families and communities—especially in marginalized populations—often bear the brunt of punitive systems due to loss of income, stigma, and systemic distrust.

A study by the RAND Corporation revealed that for low-level, nonviolent offenses, punitive measures frequently fail to meet victims' needs for acknowledgment and restitution. Deterrence sometimes relies more on the certainty of being caught than on the severity of punishment, yet lengthy sentences and harsh penalties persist despite evidence of their inefficacy.

How Does Restorative Justice Work in Practice?

Restorative justice models differ by context, but most share a similar process:

- Referral and Assessment: When a crime occurs, suitable offenders are identified (usually those with nonviolent records or first-time offenses) and evaluated for restorative suitability.

- Preparation: Facilitators brief victims, offenders, and support figures separately, gauging readiness and willingness to participate.

- Dialogue Session: In a safe, structured environment, parties share experiences and feelings. Victims explain the real impact of the crime, while offenders listen and discuss motivations.

- Agreement: Participants collaboratively decide on meaningful actions for accountability—these may include apologies, restitution, or service.

- Follow-Up: Progress is monitored, ensuring outcomes are achieved and relationships, if possible, are mended.

For example, in New Zealand's juvenile justice system, youth offending is commonly addressed through "family group conferences." These meetings involve victims, families, social workers, and the offender to craft tailored responses—often leading to lower reoffending and greater satisfaction among victims compared to traditional court sentences.

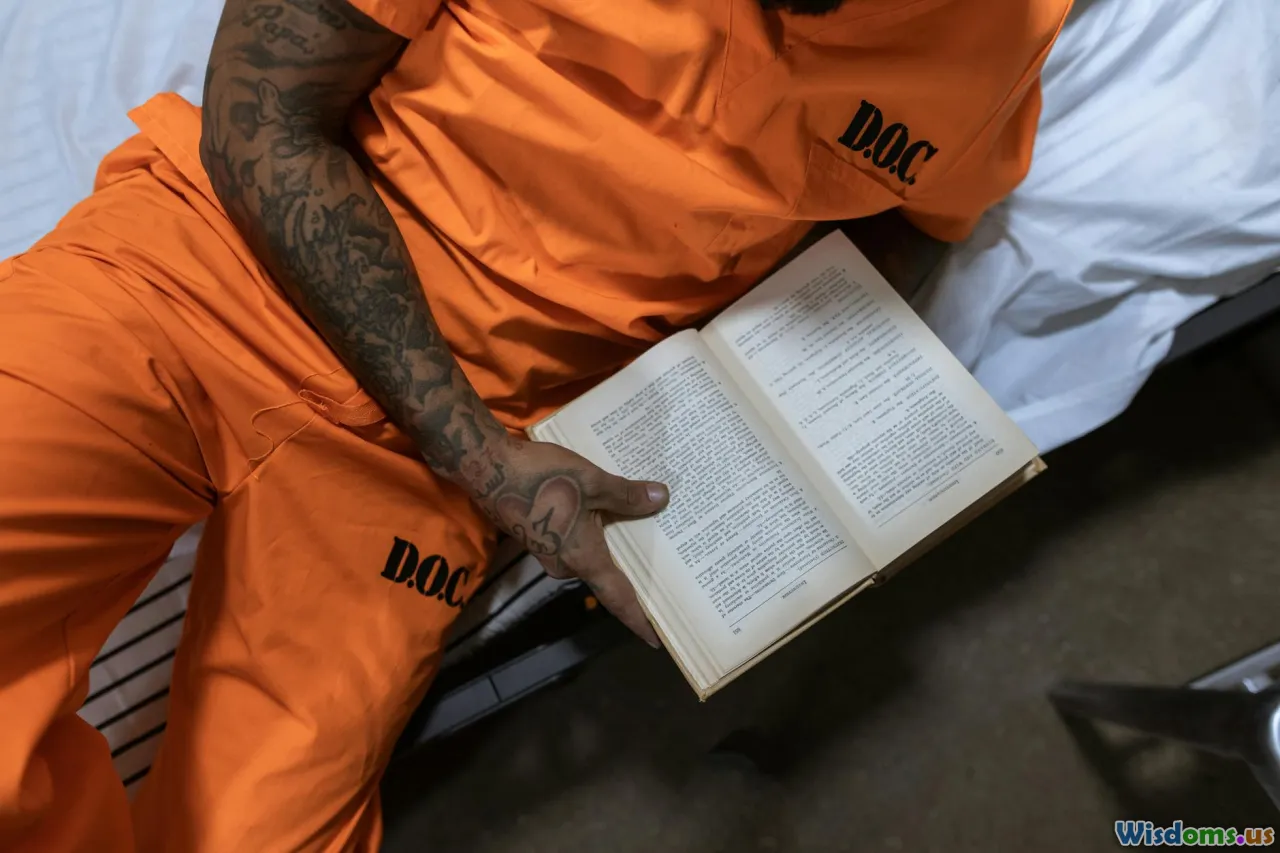

Real-World Evidence: Measuring Effectiveness

The critical question remains: does restorative justice actually work? A growing body of research suggests a cautiously optimistic answer—especially for certain crimes and contexts.

United Kingdom

The UK's Ministry of Justice funded pilot programs offering restorative conferencing as an option for low-level crimes. According to their 2017 review:

- Participants reported a 85% victim satisfaction rate (compared to about 50% through regular courts).

- Restorative approaches were associated with a 14% reduction in recidivism.

- Victims regularly cited the opportunity to voice their pain directly to offenders—and receive a tailored form of reparation—as a source of emotional closure.

United States

The Oakland Unified School District implemented restorative practices in schools. By 2018, disciplinary suspensions dropped by 47%, while graduation rates climbed, suggesting these approaches can stem the "school-to-prison pipeline."

New Zealand

Perhaps the strongest national implementation, as noted before, is in New Zealand: since launching family group conferences for youth, research shows Maori and Pasifika communities—historically overrepresented in courts—have seen more culturally relevant responses, with reoffending rates lowering by 22% over five years.

Limitations in Evidence

That said, most successes are seen with nonviolent, first-time offenders, and where communities are engaged and supported throughout implementation. Further, evaluation methods vary greatly, making apples-to-apples comparisons with traditional punishment difficult at scale.

Strengths and Benefits of Restorative Justice

Restorative justice's key strengths cannot be overstated.

1. Victim Empowerment

Victims commonly feel voiceless or sidelined in formal court processes. Restorative approaches allow them to articulate needs, receive explanations, and ask questions—experiences often pivotal for psychological healing. A meta-review in Contemporary Justice Review found that victim satisfaction is frequently two to three times higher in restorative programs than in traditional alternatives.

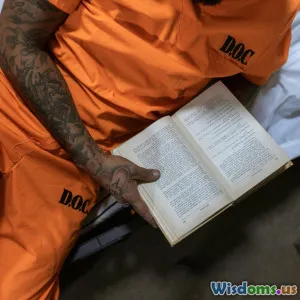

2. Offender Accountability

Unlike passive acquiescence to imposed sentences, offenders in restorative schemes must confront the humanity and suffering of their victims. Direct dialogue proves transformative for many—giving offenders ownership and insight, thus reducing "repeat" offending.

3. Community Involvement

Restorative programs pull in community members, building collective solutions and positive social norms—key in settings where crime undermines neighborhood trust.

4. Cost-Effectiveness

A study by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy concluded every dollar spent on restorative conferencing generated over eleven dollars in public benefit (from reduced reoffending and lower criminal justice costs).

Challenges and Criticisms

Not every circumstance lends itself to restorative justice. Professionals and victims flag various concerns:

1. Not Universal

Restorative justice may not be suitable for severe or violent crimes, especially those involving abuse or intimate violence. Trauma survivors may find engagement with their offender retraumatizing, or there may be dangers of manipulation or coercion.

2. Voluntary Nature

Because effective restoration relies on genuine participation, coerced apologies or insincere participation can undermine the process.

3. Uneven Access

Quality restorative programs require well-trained facilitators and infrastructure, which can be scarce in underfunded or overburdened systems. There are disparities in who gets referred to restorative options—often excluding disadvantaged demographics who might benefit most.

4. Risk of "Net-Widening"

Some critics argue that introducing restorative justice for cases otherwise destined for dismissal can paradoxically increase entrants into the criminal justice process, surveilling people who might have avoided intervention altogether.

5. Community Preparedness

Communities must be prepared to support both victims and offenders, which requires ongoing trust and sustained relationships. Where communities are fragmented or strained, such processes may fall flat.

When and Where Can Restorative Justice Replace Punishment?

So, is restorative justice a wholesale replacement for traditional punishments, or is it a strategic complement? Most evidence suggests its greatest promise lies in three key zones:

1. Juvenile Offenses

Adolescents' higher plasticity and ability to grow through accountability makes restorative justice a gold standard for many young offenders. Countries like Belgium, Norway, and New Zealand have adopted these processes with excellent progress in reducing youth incarceration and recidivism.

2. First-Time or Low-Level Offenses

Cases of theft, property damage, and some assaults can be more productively addressed through restoration. Communities in Norway and Australia report reduced recidivism and fewer negative side-effects when using these models at early justice stages.

3. Specific Community Contexts

In close-knit or culturally resilient settings, restorative justice can rebuild or strengthen bonds damaged by minor crime, supporting true community policing.

But critics caution that for serial, violent, or high-risk offenses, some level of incapacitation and formal adjudication remains essential—both for public safety and the needs of survivors who are not ready or able to engage in restorative dialogue.

Building an Integrated Future: How to Blend the Best of Both Systems

The emerging consensus among practitioners is not that one system must "replace" the other, but that a more just society seeks integration.

Policy Design Tips

- Screening Protocols: Use careful evaluation to determine which cases are suitable for restorative options without compromising safety.

- Pre-Sentencing Diversions: Allow initial offenses to be addressed restoratively, resorting to customary justice if offenders do not meet agreements.

- Victim Consent and Choice: Empower victims with options—restorative or traditional. Mandating one model denies agency.

- Long-Term Evaluation: Establish independent monitoring bodies to assess long-term impact on recidivism, healing, and public confidence.

- Investment in Community Infrastructure: Restorative models thrive in communities with resources for facilitation, mental health, and peer support—investment here multiplies restorative solution effectiveness.

Countries and cities experimenting with these hybrid models—from Canada’s Indigenous courts to city-based restorative boards in Colorado—show it’s possible.

Looking Forward: Restoring Justice with Humanity

The shift towards restorative justice is more than procedural reform—it is a philosophical transformation. Healing over punishment, truth over silence, and hope over alienation: these are the pillars upon which modern communities, striving for both safety and compassion, can flourish. While it is unlikely that restorative justice will ever fully replace all forms of traditional punishment, its successes argue for a future where restoration and accountability walk hand in hand. In a continually evolving justice system, the question may become not if, but how broadly we choose to restore.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Other posts in Criminal Justice System

Popular Posts