Unpacking Social Learning Theory in Modern Urban Crime

13 min read Explore how social learning theory explains crime patterns in today's cities, linking peer influence, media, and community with urban youth behavior. (0 Reviews)

Unpacking Social Learning Theory in Modern Urban Crime

Introduction: Why Do Urban Crimes Spread Like Wildfire?

If urban crime were a rumor, how quickly would it catch on? In bustling cities, patterns of criminal behavior often appear to erupt, spread, and evolve almost like social trends. But why? At the heart of this question lies Social Learning Theory, a framework that reaches beyond police sirens and courtroom scenes into the hidden network of influences that shape behavior. In today's digitally connected, densely populated cities, Social Learning Theory helps decode why some neighborhoods see repeated cycles of crime and how criminal acts can ripple through peer groups, social media, and entire communities. Let’s dive into how this theory unravels the web of urban crime, why it matters today, and what we can do about it.

What is Social Learning Theory?

Social Learning Theory (SLT), first systematized by Albert Bandura in the 1960s, posits that people develop behaviors, values, and attitudes primarily by observing and imitating others, especially those they consider role models. While originally rooted in psychology, the theory found fertile ground in criminology through the work of Ronald Akers, who adapted it to explore the formation of criminal behavior.

Key Principles

- Observation & Modeling: We mimic behaviors we see in others, particularly those reinforced or rewarded in some way.

- Differential Association: Who we associate with influences what we learn and practice, especially in formative years.

- Imitation & Reinforcement: Behaviors that receive positive feedback (for example, status among peers or tangible rewards) are more likely to be repeated.

- Cognitive Processes: Individuals process observed actions and weigh outcomes, which guides their own choices.

Let's see how these principles take center stage in urban environments.

Peers, Neighborhoods, and Crime: SLT in the Urban Jungle

How Environments Shape Behaviors

Bustling neighborhoods, sprawling housing estates, and social hotspots in the city offer a fertile backdrop for the transmission of behaviors. In many urban centers, dense living conditions converge with poverty, limited opportunities, and fragmented social controls—creating circumstances ripe for illegal acts to be observed, considered, and often copied.

Example: Chicago’s Gang Networks

Sociological studies of Chicago's neighborhoods reveal how youth growing up in environments dominated by gang presence frequently view these groups as both community and pathway. They witness, firsthand, that gang members enjoy forms of respect, economic gain, or protection—rewards that reinforce such behaviors according to SLT. Thus, criminal conduct is less a unique act than part of a learned script, passed peer-to-peer.

Data Snapshot:

- In a 2021 study published by the American Journal of Sociology, youth in neighborhoods with high gang densities were 2.4 times more likely to report being exposed to criminal behavior in daily life compared to those in low-density areas.

“Code of the Streets”: A Case from Philadelphia

In his influential work "Code of the Street," Elijah Anderson details how kids in certain urban neighborhoods internalize a parallel set of values—what's respected on the street differs from the law. Here, conflict is often solved by violence or intimidation, modeled and reinforced by older peers or family members. Social Learning Theory accurately describes these dynamics: observing violence as a means to an end, and learning that respect is obtained through aggressive acts.

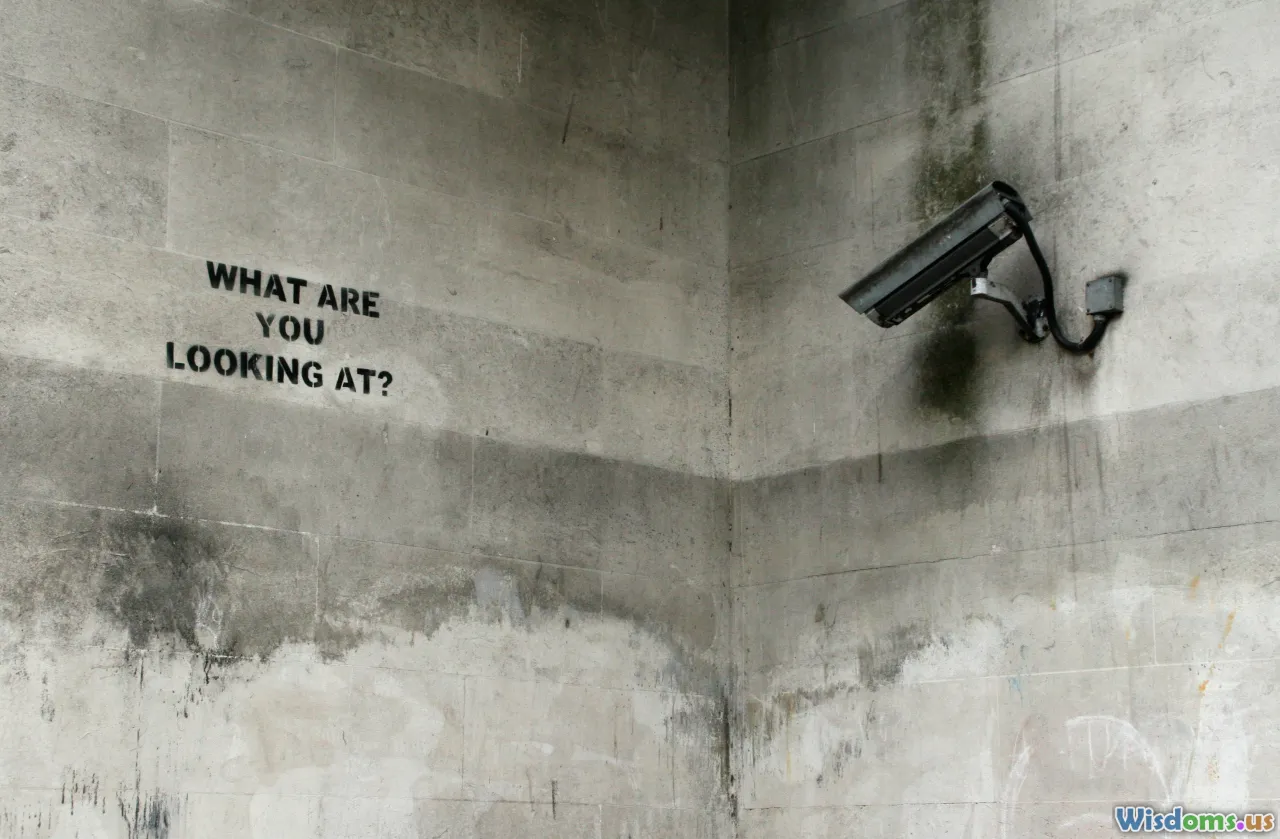

Force Multipliers in Modern Times: The Digital Urban Classroom

Social Media’s Role in Urban Crime Transmission

Today’s “street corners” stretch far beyond geography—digital spaces like TikTok, Instagram, or encrypted chat groups are virtual neighborhood meeting points. Social media allows the modeling and glamorization of criminal behaviors to reach wider audiences at unprecedented speed.

Example: Viral Crimes

Take the phenomenon of "flash mobs" or spontaneous group thefts—sometimes dubbed "flash robs." In recent years, coordinated shoplifting incidents have swept through American cities. After one group publicizes its exploits on social media, others, emboldened and inspired, replicate these acts, striving for online notoriety. The pattern aligns almost perfectly with SLT’s focus on imitation and reinforcement.

Real-World Quote

“Social media has made our job 10 times harder. A video can spark dozens of copycat incidents overnight.” — Sergeant J. Martinez, San Francisco Police Dept.

Supporting Fact:

- The National Retail Federation reported a 26% year-to-year increase in organized retail crime in 2023, with police linking many waves of incidents directly to viral social media content.

Online Gang Recruitment

Recruitment rituals, previously hidden and local, have expanded online. Gangs in cities like Los Angeles or London now use encrypted messaging, YouTube music videos, and Instagram stories to showcase status, promising belonging or easy money to susceptible youth. For many, virtual observation is the first step toward real-world action.

Breaking Down the “Learning Environment” of Urban Youth

School, Streets, and Survival

Not all urban environments predispose kids equally to crime. Schools, after-school programs, community centers, and crime prevention clubs can counter negative influences by providing constructive peers, role models, and rewards. Yet, when these supports are absent or under-resourced, youth lean more heavily on peer groups and the lessons reinforced in the street.

Evidence from New York City

- A 2019 NYC Department of Youth study found that high school students with access to mentorship programs were 35% less likely to be involved in group-related offenses than those without such support. The pull to crime weakens when alternative models and positive reinforcement exist.

Family Influences

Family systems transmit lessons about “what works” in the city: coping, survival, morals, or shortcuts. Households where members have previous criminal histories unintentionally model and normalize illegal behaviors, particularly if criminal acts are viewed as necessary or justified.

Example:

In neighborhoods affected by mass incarceration, absence of adult role models often leaves younger siblings to mimic older, sometimes absent, brothers or cousins. This creates intergenerational cycles, detailed in studies from Baltimore to Manchester, UK.

Role of Community Leaders and Influencers

Modern cities are witnessing the rise of credible messengers—ex-gang members, activists, or mediators who use their past to model positive change. Their imprint can disrupt the negative cycles that SLT describes.

“You can’t just tell youth to stop. You have to show them a different way.”—Shanduke McPhatter, former NYC gang member and founder, Gangstas Making Astronomical Community Changes (GANGSTAS INC.)

Impact Snapshot

Programs employing community messengers in Chicago and London have reduced retaliatory shootings and group violence by as much as 31%, according to recent Urban Institute evaluations.

Interventions: What Works Against Socially Learned Crime?

Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches

Modern intervention programs often combine SLT principles with cognitive-behavioral strategies. They seek to interrupt cycles of criminal conduct by teaching impulse control, conflict resolution, and new avenues for respect and status—demonstrated through mentors, group sessions, or skill-building workshops.

Success in Glasgow, Scotland

A remarkable reduction in youth gang violence in Glasgow occurred after the city piloted street-level mentorship and constructive community projects. Violent incidents fell by 46% from 2005 to 2015, largely attributed to the “violence interrupters” model inspired by SLT.

Police and Community Partnership Programs

Community policing now incorporates social learning by engaging trusted local figures to model compliance, respect, and law-abiding behavior. Police-youth dialogues, joint social projects, and restorative justice programs encourage cooperative relationships rather than only punitive responses.

Example: Cure Violence, Chicago

Initiatives such as Cure Violence train former offenders as "violence interrupters," who mediate conflicts before they explode. Rather than acting as enforcers, these figures exemplify change and offer real alternatives, reducing shootings in targeted areas by up to 63%. (CDC, 2017)

Digital Countermeasures

Recognizing the role of digital peer influence, some cities fund campaigns where local influencers challenge criminal glamorization, instead showcasing stories of legal success, entrepreneurship, and community pride. Technology is leveraged to “inoculate” at-risk youth against the allure of glorified urban crime.

Why Does Social Learning Theory Matter Now?

Tackling Persistent Urban Challenges

Urban spaces magnify social learning for better or worse. Without effective intervention, cycles of imitation and reinforcement can spiral unchecked, creating persistent crime hotspots. But with understanding comes hope: targeting the levers of social learning can reshape entire city blocks.

The Data Speaks

- Violence Interruptor Programs: Reduced shooting victimizations by >40% in key NYC sites (John Jay College, 2021).

- After-school Mentorship: Correlated with up to 60% drop in youth crime hotspots (Harvard School of Public Health, 2019).

- Digital Outreach Initiatives: 33% less likely for at-risk teens to report considering crime after exposure to positive role models online (Pew Research Center, 2022).

Conclusion: Learning, Unlearning, and Hope

Urban crime isn’t just the product of scarcity or broken windows; it emerges and evolves as youth and adults watch, learn, and repeat. Social Learning Theory offers a powerful lens to understand not simply why crime happens, but how cycles perpetuate and, crucially, how they can be broken.

The solutions lie not only in policing, but in amplifying positive models, shrinking the digital echo chambers of criminal glorification, and ensuring every child encounters alternative scripts for success. As cities move forward—denser, more digital, more diverse than ever—the tools for prevention, interruption, and transformation will depend heavily on harnessing the invisible power of social learning.

Whether you’re a policymaker, a teacher, or a concerned neighbor, understanding how behaviors are learned (and unlearned) is the key to safer, stronger cities for all.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts