What Ancient Egypt Can Teach Us About Barter and Value Assignment

9 min read Discover how Ancient Egypt's barter system and value assignment offer timeless lessons on trade, economy, and trust. (0 Reviews)

What Ancient Egypt Can Teach Us About Barter and Value Assignment

Introduction

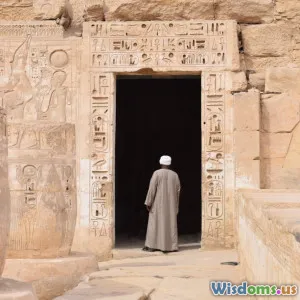

Imagine a bustling marketplace, not unlike today’s outdoor farmers' markets but set thousands of years ago on the fertile banks of the Nile. Ancient Egypt, one of the oldest and most sophisticated civilizations, was a hub of commerce where barter thrived prior to the advent of currency as we know it. This system of direct exchange, coupled with unique methods of assigning value to goods and services, offers profound insights for today’s economy and intercultural trade.

By examining Ancient Egypt’s barter system, we reveal economic principles rooted in reciprocity, trust, and social organization—principles that remain relevant today. Whether you're an economist, business professional, or history enthusiast, exploring this ancient world uncovers lessons about assigning value beyond modern money, and the social bonds that sustained complex trade networks.

The Foundations of Barter in Ancient Egypt

Bartering—the direct exchange of goods and services—is considered the earliest form of trade. While many associate economies with coinage or bills, Ancient Egypt’s society thrived long before widespread monetary systems. For centuries, Egyptians exchanged grains for pottery, linen for labor, and cattle for beer.

The Agricultural Economy and Necessity for Exchange

Egypt’s economy was initially agrarian-based. The predictable flooding of the Nile provided fertile soil, allowing farmers to produce surplus grain. However, not every Egyptian could produce everything needed for their survival, inciting the requirement for exchange. Artisans needed food; farmers needed crafted tools and cloth; no single individual or community was self-sufficient.

This created fertile ground for barter systems to emerge, balancing logistical constraints and fostering community interdependence. The barter remained an organic mechanism responding to immediate needs rather than abstract monetary value.

Example: Grain and Pottery Exchange

Farmers typically traded grain for pottery supplies. Pottery was critical for storage and transport, but pottery craftsmen depended on grain for subsistence. Archaeological records from sites like Abydos reveal trade agreements where specified quantities of grain were exchanged for a given number of pots—demonstrating precise value assignment according to utility and availability.

Complex Value Assignment Beyond Simple Exchange

Barter systems are often viewed as crude or unsophisticated, but Ancient Egypt debunks this stereotype with evidence of nuanced value assignment informed by utility, scarcity, and social status.

Measuring Value by Quantity and Quality

Contracts documented on papyri elucidate how goods were assigned explicit worth, e.g., a measure of grain equaling a luxury textile piece. Economic actors negotiated values with understood standards, such as weight measures like the deben (approximately 91 grams) used to establish equivalencies.

In addition to quantity, quality greatly influenced valuation. For instance, red ochre pigment used in temple art required more labor and was rarer than standard earth pigments, fetching higher barter value. This differentiation indicates a sophisticated appraisal beyond mere counting.

Social and Religious Factors in Trade

Trading wasn’t only economic but also social and sacred. Certain goods like precious metals or crafted amulets held spiritual significance. Their value wasn’t purely utilitarian but embedded in social hierarchy and divine favor.

Priests and administrators regulated exchange to ensure fairness and preserve religious honor. The concept of maat (order and justice) permeated commerce, influencing honest value assignment and dispute resolution.

Archaeological Insight: The Amarna Letters

Arabic correspondence more than 3,000 years ago, collectively known as the Amarna Letters, reveal diplomatic barter agreements where Egyptian rulers exchanged gold and tribute with neighboring kingdoms. These international exchanges display assigned value on items beyond everyday goods, further underlining the barter system’s adaptability.

Trust and Record-Keeping: The Necessary Glue

How did Egyptians ensure fair trade when barter depended heavily on subjective value? The answer lies in their pioneering record-keeping.

Accounting Records on Papyrus

Egyptians were among the first to maintain detailed bookkeeping using hieratic script on papyrus. Storage houses documented incoming and outgoing goods with specificity. These tangible records fulfilled crucial roles: reducing disputes, standardizing values, and promoting trust.

The House of Life, linked to temple complexes, served as bureaucratic hubs that monitored trade agreements and crop yields, thereby supporting transparent transactions.

Token Systems as Precursors to Currency

Archaeologists discovered clay tokens and seal impressions used to represent quantities of goods, possibly acting as physical claims or promissory notes. Such token economies created trust by providing a tangible claim over barter value without immediate exchange, foreshadowing the use of coinage.

Lessons for Modern Economic Systems

What can this history teach today’s fast-paced, currency-driven economies?

Valuing Utility Over Price Tags

Commodity trading in modern markets often prioritizes price volatility and speculative values over intrinsic utility. Ancient Egyptians assessed exchange based squarely on tangible need and perceived utility—before artificial constructs of price dominated. A reminder exists here to evaluate goods and services based on their practical worth and sustainability.

The Power of Trust and Documentation

Ancient record-keeping exemplifies that trust is foundational to any exchange system—be it barter or fiat currencies. In today’s digital age, blockchain technologies fulfilling similar roles demonstrate the continued necessity of transparent, secure record systems to ensure fairness.

Considering Social and Ethical Dimensions

Modern trade can learn from the Ancient Egyptian integration of social ethics and spirituality into economics. Values like fairness (maat) and respect for communal harmony could inform contemporary discussions on corporate social responsibility and ethical trade.

Barter Revival in Contemporary Contexts

Interest in barter systems is resurging, especially in economic downturns or localized communities. Technologies enabling online barter and time banking reflect smiles towards ancient practices. Understanding how Ancient Egypt assigned value and fostered trust can enhance these modern initiatives with tried and tested principles.

Conclusion

Ancient Egypt provides a striking example of how stampeding commerce depended not just on goods, but on social conditions, cultural values, and methodical record-keeping. Their barter system was dynamic, nuanced, and intertwined with ethical norms that ensured equitable value assignment.

By studying these practices, we gain more than historical knowledge—we acquire frameworks for rethinking value, encouraging trust, and fostering sustainable exchange networks in a world that sometimes feels dominated by impersonal monetary transactions.

Rediscovering the lessons of Ancient Egypt can inspire modern economies to balance utility, fairness, and community connection—principles essential for economic resilience and human dignity.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts