Trading Across Deserts The Hidden Routes of Arabia

11 min read Explore the secret ancient caravan paths of Arabia, uncovering how deserts shaped trade, culture, and economies across millennia. (0 Reviews)

Trading Across Deserts: The Hidden Routes of Arabia

Introduction

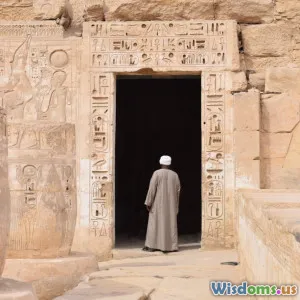

Beneath the relentless sun and sprawling sands of the Arabian Peninsula lies a tapestry of ancient trade routes, weaving stories of daring caravans, exotic goods, and cultural exchanges. For thousands of years, these pathways—often overlooked in mainstream history—served as critical arteries connecting disparate civilizations across deserts. Imagine camel caravans snaking silently across dunes, carrying frankincense, spices, gold, and silk from the remote ports of Oman to the bustling markets of the Levant and beyond. The social and economic significance of these routes transcended mere commerce; they shaped language, religion, and political power. This article ventures deep into the hidden desert routes of Arabia, uncovering their history, complexity, and lasting legacy.

The Geography of Arabian Trade Routes

Nature’s Challenge: The Arabian Desert

The Arabian Peninsula is predominantly desert—home to the Rub' al Khali, also known as the Empty Quarter, the largest continuous sand desert on Earth, covering over 650,000 square kilometers. Traveling across such harsh landscapes was a feat in itself. Extreme heat, lack of water, and shifting dunes created formidable challenges for traders and their camels.

However, natural formations like oases—e.g., Al-Ahsa and Al-Ula—and mountain ranges such as the Sarawat provided crucial waypoints. These geographic features guided traders, offering rest and resources essential for survival.

Hidden Networks Connecting Key Centers

Unlike the well-known Silk Road spanning from China to Europe, Arabian trade relied on desert crossings linking key urban centers, including Petra, Palmyra, and Mecca, with coastal ports on the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. Several significant routes stand out:

- Incense Route: Running from southern Arabia (modern Yemen) to the Mediterranean, this route facilitated the trade of frankincense and myrrh, highly prized in religious and cultural rituals.

- Gulf Road: Connecting the Persian Gulf ports through Bahrain and Qatar to the interior, instrumental for pearls, spices, and textiles.

- Dabba-Ghassan Route: A lesser-known but vital passage connecting the interior desert to the Red Sea coast.

Each of these paths utilized topographical knowledge to maximize safety and efficiency in trade.

Historical Significance of Arabian Desert Trade

Economic Impact

The Arabian desert trade routes became instrumental economic corridors from as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. Regions like the ancient kingdom of Saba (Sheba) thrived due to their control over spice and incense resources. This control allowed them to dominate the lucrative trade with Egypt, Mesopotamia, and later Rome.

A Roman text, the "Periplus of the Erythraean Sea," written around the 1st century CE, detailed how precious commodities such as frankincense, aloe, and spices were transported from Arabia through desert routes to Mediterranean markets.

The economic importance was immense; Frankincense alone accounted for the wealth of entire kingdoms, fueling monumental architecture and armies. Camels, aptly known as the 'ships of the desert,' made these transactions possible with their endurance.

Cultural and Religious Exchanges

Trade was not just about goods. Along these routes, ideas, languages, and religious beliefs spread crucially. For example, the Nabataeans, who controlled Petra, developed a unique culture influenced by Arab, Greek, and Roman elements. Their script and advanced water management systems demonstrate the blending of knowledge.

Mecca’s rise as a mercantile hub is tightly linked to these caravan routes. Before Islam, Mecca was a pilgrimage and trade center, where different Arabian tribes interacted. These connections arguably laid the groundwork for Islam’s rapid spread in the 7th century.

Political Power and Control

Control over these routes was synonymous with political power. Various empires and tribal confederations sought dominance. The Himyarite Kingdom held sway over southern trading hubs while the Byzantine and Sasanian empires tried to control northern segments.

The strategic importance of controlling desert routes was so paramount that this played a key role in Arab tribal alliances and Muslim conquests, where gaining trade dominance equated to asserting sovereignty.

The Mechanics of Desert Trading

The Caravan Culture

Long caravans of camels and donkeys, often escorted by armed guards, braved perilous desert conditions. A typical caravan could consist of dozens or even hundreds of animals, carrying highly valuable and perishable goods.

Experienced guides, called "naqibs," navigated by stars and landscape memory. Camel drivers had intricate knowledge of water sources, enabling survival over days without resupply.

These caravans often synchronized travel for safety in numbers and to utilize seasonal winds. For instance, the monsoon winds influenced sea trade links between Arabia and India, tightly coordinating with desert route timings.

Goods Exchanged

Among the revered commodities were:

- Frankincense and Myrrh: Resinous gums used in religious rituals across the ancient world.

- Silk and Spices: Imported from India and Southeast Asia, these luxury goods were traded across the peninsula.

- Gold and Precious Stones: Earthly wealth that was transported both ways.

- Textiles and Pottery: Both functional and decorative, representing cultural interchanges.

Historical records and archaeological finds, such as those from Timna Valley, show evidence of extensive metal trade and craftsmanship fueled by desert commerce.

Innovations Facilitating Trade

The domestication of the Arabian camel (Camelus dromedarius) was revolutionary—its ability to endure long journeys without water supplemented by camel caravan techniques made desert trade feasible.

Moreover, innovations in water management, such as the presence of wells (qanats) and water cisterns, not only supported trade but also permanent settlements and oasis life.

Case Studies: Key Hidden Routes and Their Impact

The Incense Route

Starting in the Dhofar mountains of Oman and Yemen, this ancient route transported frankincense across 3,000 km to the ports of Gaza and Aqaba. Ninety percent of the incense consumed in the Roman Empire came through this path.

Archaeological evidence like caravanserais (roadside inns) at places like Shisr in Oman provides insights into the scale and organization of trade.

The Najd Desert Corridors

Less discussed but equally important, this network in central Arabia connected eastern trade to Mecca and Medina. Control of these desert passes helped the emerging Islamic empire harness economic power swiftly.

Petra and Palmyra: Oasis Crossroads

Both cities flourished as trading hubs and display remarkable urban infrastructure adapted to desert extremes. Petra’s water channels and tombs capture how wealth from desert trade created archaeological marvels still studied today.

Decline and Legacy

With the advent of maritime routes during the Age of Exploration, especially after Vasco da Gama’s trip to India around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope in the late 15th century, sea routes began to overshadow desert caravans.

Moreover, the rise of modern nation-states and later petroleum discoveries reoriented economic patterns in Arabia. However, the legacy of these desert trading routes survives culturally and archaeologically—as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, in oral histories, and ongoing regional studies.

Moreover, recent initiatives like Saudi Arabia’s "Desert Renewal" projects seek to revive and preserve caravan heritage, recognizing their importance for tourism, national identity, and education.

Conclusion

The hidden trade routes of the Arabian deserts are far more than lost pathways across sand and rocks. They embody human resilience, economic ingenuity, and the enduring human desire to connect and share. From frankincense-laden caravans to the rise of powerful cities like Petra and Mecca, these trails demonstrate how deserts, often perceived as barren, were centers of vibrancy and exchange—crucial threads in the tapestry of world history. Embracing and understanding these ancient routes offers modern readers a profound appreciation of how geography shapes civilization.

Acknowledging these routes reminds us that deserts are not just obstacles but bridges—silent witnesses to the flow of goods, ideas, and cultures across time.

“Trade has been a cornerstone of civilization, and nowhere is this truer than in the deserts of Arabia, where the flow of goods also nurtured the flow of knowledge and culture.” — Dr. Amina Al-Sabra, Middle Eastern Historian

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts