From Spices to Silk The Ultimate Guide to Ancient Luxury Goods Trade

9 min read Explore the intricate trade of ancient luxury goods like spices and silk, revealing how these coveted commodities shaped world history and cultural exchange. (0 Reviews)

From Spices to Silk: The Ultimate Guide to Ancient Luxury Goods Trade

Introduction: The Allure of Ancient Luxuries

Imagine a world where an ounce of cinnamon would equate to a king's ransom, and fine silk garments were the upper crust’s symbol of status and power. Long before industrial manufacturing, ancient luxury goods like spices and silk not only tantalized the senses but were also engines of early globalization. This article charts the remarkable journey of these coveted commodities, exploring how their trade impacted economies, cultures, and geopolitics in antiquity.

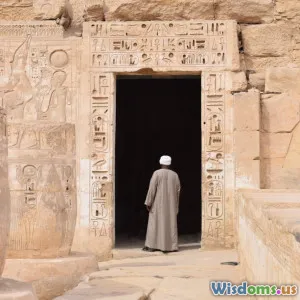

Luxury goods such as spices and silk exemplify the ingenuity and interconnectedness of early civilizations. From the bustling markets of Alexandria to the winding caravan trails of the Silk Road, these goods underpinned commerce, diplomacy, and even religion, serving roles far beyond mere adornment or flavor. Let’s delve into the depths of this ancient trade network to uncover its secrets, challenges, and legacy.

The Historical Context of Ancient Luxury Goods

In ancient times, luxury was defined not simply by aesthetic appeal but by rarity and function. Spices and silk represented two pinnacle commodities—valued for their sensory delight, medicinal qualities, or technological marvel.

The Significance of Spices

Spices like cinnamon, pepper, cardamom, and frankincense were treasured for flavoring food, preserving it, and for their use in rituals and medicine. For example, ancient Egyptians used frankincense and myrrh extensively in embalming and religious ceremonies, highlighting spices' sacred dimension.

Trade in spices is traced back to the Bronze Age (~3000 BCE), with Indian Ocean routes connecting East Africa, Arabia, India, and Southeast Asia. The Greeks and Romans imported spices through intermediaries in Arabia and Egypt, who controlled key maritime chokepoints like the Red Sea.

The Magic of Silk

Silk, a shimmering natural fiber produced by silkworms, originated in China at least 4,000 years ago. The luxurious fabric stood apart for its unmatched softness, strength, and vibrant colors, gracing emperors and elites.

China’s strict monopoly on silk production turned the commodity into a diplomatic and economic weapon. Legends suggest that even Roman emperors coveted silk so much that large quantities drained the empire’s silver reserves. The demand for silk catalyzed the creation of vast trade routes, later known collectively as the Silk Road.

Trade Routes: Pathways of Prosperity

Ancient luxury goods depended on intricate and often perilous trade routes linking producers to distant consumers. Two major networks dominated the exchange of spices and silk.

The Spice Routes

Early spice routes focused on the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, and overland corridors like the Incense Route.

-

Maritime routes: Facilitated by predictable monsoon winds, they connected East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, India, and Southeast Asia. Ports like Aden, Calicut, and Malacca flourished.

-

The Incense Route: A caravan trail from southern Arabia through Petra to Mediterranean ports where spices and frankincense were highly coveted, especially in the Roman Empire.

The value chain was complex. For instance, black pepper native to the Malabar Coast of India passed through Arab merchants who supplied the Roman markets. Pliny the Elder, a first-century Roman naturalist, lamented the high prices and widespread use of exotic spices.

The Silk Road

Stretching over 4,000 miles, the Silk Road was not a single road but a network running from Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in China through Central Asia to the Mediterranean.

- This route united regions as far-flung as Korea, India, Persia, and Greece.

- Caravans carried not only silk but also precious stones, metals, glassware, and ideas.

Despite its name, the Silk Road was bi-directional; Buddhist texts, agricultural products, and inventions like papermaking traveled westward, while gold, silver, and grapevines traveled eastward. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus praised silk’s beauty but criticized its effect on Roman morals and economics.

Challenges Along the Trade Networks

Transporting precious goods across deserts, mountains, and seas was fraught with peril.

Geopolitical Hindrances

Control over trade routes often sparked conflict. The Roman-Parthian rivalry partially centered on controlling eastern trade arteries. Similarly, Indian and Southeast Asian port cities frequently engaged in naval skirmishes to dominate the spice trade.

Logistical Challenges

Ancient traders faced geographic barriers like the Taklamakan Desert or the Horn of Africa’s rough seas. Caravans had to carry essentials for survival—water, food, and pack animals—alongside luxury goods worth their weight in gold.

Preservation and Duplication

Preserving spices was vital; for example, pepper was dried and stored to retain flavor. Silk required careful processing to avoid damage. Additionally, counterfeit goods could devalue markets; Chinese silk was fiercely guarded against replication, while spice adulteration remained common.

Impact on Ancient Civilizations

Trade in luxury goods transcended commerce, shaping the cultural and technological fabric of societies.

Economic Prosperity

Cities like Palmyra and Petra thrived as key nexus points, gaining wealth and political influence. Alexandria became a cosmopolitan hub where traders, scholars, and artisans mingled.

Cultural Exchange and Innovation

Luxury trade allowed the spread of art styles, religious beliefs, and technologies. For example, Buddha statues along the Silk Road exhibit Greek artistic influence from Alexander the Great’s campaigns. Papermaking spread westward, accelerating knowledge dissemination.

Diplomacy and Power Symbolism

Gift exchanges of spices and silk solidified alliances and vassal relationships. Qin Dynasty emperors used silk for court robes to emphasize divine right; Roman elites flaunted spices at banquets signaling their affluence.

Societal Transformations

Demand for luxury goods stimulated agricultural innovation (e.g., spice cultivation in tropical climates), craftsmanship advances, and even social stratification through access to elite commodities.

Legacy of Ancient Luxury Goods Trade

Today’s global consumer culture traces lineage to these ancient markets.

- Modern spice consumption patterns reflect millennia of cultivation and preferences shaped by historical trade.

- Silk production continues as an artisanal and commercial industry across China, India, and beyond.

- The Silk Road itself serves as a metaphor for globalization and intercultural dialogue.

Scholars like Peter Frankopan, in his book The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, emphasize how these ancient networks rewrote history away from Eurocentric narratives, highlighting Asia’s centrality.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Fabric or Flavor

The journey from spices to silk traces humanity’s enduring quest for beauty, taste, and connection. Far from mere commodities, these luxury goods were catalysts for economic integration, cultural synthesis, and technological creativity. Recognizing their impact enriches our understanding of global history and the foundations of today’s interconnected world.

Next time you savor a pinch of pepper or admire a silk scarf, remember you're engaging with a legacy spanning continents and centuries—a testament to human curiosity and enterprise.

References & Further Reading:

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History

- Frankopan, Peter. The Silk Roads: A New History of the World

- Young, Gary K. Rome’s Eastern Trade

- Liu, Xinru. The Silk Road in World History

- UNESCO Silk Road Programme

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts