Did Spices Really Ignite Ancient Economic Booms

9 min read Exploring how spices shaped ancient economic booms through trade, culture, and global connectivity. (0 Reviews)

Did Spices Really Ignite Ancient Economic Booms?

Introduction

Imagine navigating vast seas and endless deserts for cargo that smelled like the very essence of the exotic—musky cinnamon, fiery peppercorns, fragrant cloves, and pungent nutmeg. For thousands of years, spices were more than kitchen ingredients; they were treasured commodities that shaped trade networks, wealth empires, and even the course of history. But did these aromatic marvels truly ignite ancient economic booms, or have historians romanticized their impact?

This article dives into the fascinating world of spice trade, unraveling how these tiny treasures sparked profound economic transformations across continents. By examining trade routes, historical accounts, economic data, and cultural influences, we aim to unveil the real role spices played in jump-starting ancient economies.

The Allure of Spices: Beyond Taste

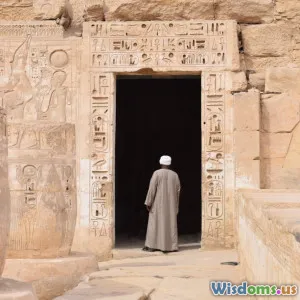

Spices captivated ancient civilizations for reasons far beyond culinary flavor. They preserved food, masked odor, held medicinal value, and even served religious and ceremonial purposes. The Egyptians, for instance, used frankincense and myrrh in embalming rituals, indicating spices' cultural importance.

Their rarity and the difficulties in sourcing them inflated their value, making spices precious like gold and silver. This high value incentivized long and perilous journeys, connecting distant societies from the Maluku Islands in Indonesia—the famed “Spice Islands”—to Roman and Greek empires and later the Arabian Peninsula.

Historical Value and Cultural Significance

- Preservation and Medicine: Before refrigeration, spices such as black pepper helped in preserving meat and fish. Ayurvedic medicine prized spices for healing, as seen in early Indian texts.

- Religious and Ceremonial Use: Incense and fragrant spices were integral to spiritual rituals in ancient Egyptian, Indian, and Chinese societies.

- Luxury Symbols: Among the Romans and later Europeans, spices symbolized status and wealth, often found at elite banquets.

Ancient Trade Routes Fueled by Spices

The story of spices igniting economies is inseparable from the networks that ferried these goods across continents.

The Overland Routes: The Silk Road's Spice Segment

Beyond silks and precious stones, parts of the Silk Road transported spices like cinnamon, cassia, and pepper. Caravans traversed from South Asia, through Central Asia, to the Mediterranean, connecting producers with consumers. Though slow and expensive, this route formed a critical early economic artery.

Maritime Spice Routes

The maritime spice route linked Southeast Asia with India, the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa. Indian Ocean monsoons allowed predictable yearly voyages, facilitating spice trading cities' flourish—like Calicut (India) and Aden (Yemen).

By the 1st century CE, Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder extolled the value of black pepper and other spices, highlighting their economic prominence.

The Arab Middlemen

Arab merchants dominated spice trade for centuries, cleverly monopolizing routes and acting as intermediaries between East and West. Their control brought enormous wealth to cities like Mecca and later Cairo during medieval periods, stimulating urban growth and economic complexity.

Spices and Economic Booms: Case Studies

The Roman Spice Economy

Romans consumed huge quantities of spices, demonstrated by archaeological finds of peppercorns in Pompeii. Estimates indicate that the Roman Empire imported approximately 100 tons of black pepper annually. This enormous demand created wealth for traders and agriculturalists, generating a multiplier effect in Mediterranean economics.

Yet, this trade was so costly that arms and gold often flowed eastwards, prompting economic imbalances. Some scholars argue these outflows pressured Rome’s economy, but simultaneously fueled an incentive to explore new routes—planting seeds for future economic undertakings.

The Medieval European Spice Boom

During the Middle Ages, spices like cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg became marvels of European courts and churches, inciting a booming demand surge.

- Venetian Wealth: Venice’s rise as a dominant maritime power is tightly linked to its control over spice imports in the 13th–15th centuries. Venetian merchants profited handsomely from distributing spices across Europe.

- Commercial Expansion: High spice demand helped finance exploratory ventures by the Portuguese and Spanish in the late 15th century. Vasco da Gama’s 1498 sea route to India directly connected Europeans to spice sources, kickstarting an era of global trade dominance.

The Impact on Southeast Asia

The lucrative spice trade transformed small island communities in the Maluku Islands. Archaeological and historical evidence reveals political centralization, wealth accumulation, and increased conflict as societies vied to control spice-producing lands.

For example, rulers in Ternate and Tidore asserted greater control with wealth from cloves, fueling warfare but also state-building processes, which historians interpret as early economic development drivers.

Economic Principles Illustrated by Spice Trade

Supply, Demand, and Monopoly

Spices practically exemplified early global capitalism concepts:

- Scarcity Induced Value: Limited geographic sources created scarcity, driving prices extraordinarily high.

- Monopolistic Control: Entities like Arab traders and Venetian merchants controlled supply, driving prices and profits up.

- Long-Distance Risks and Rewards: Dangers posed by long transport routes justified high prices but also incentivized efficient trade networks and innovation.

Capital Accumulation and Investment

Ledgers from medieval merchants demonstrate reinvestment of spice profits into ships, fortifications, and urban infrastructure, indicating economic multiplier effects beyond direct trade.

Global Economic Interconnection

The spice trade was a key vector for globalization long before modern conceptions. It linked disparate economies, facilitated cultural exchanges, and helped spread technology.

Challenges and Limits: Did Spices Singlehandedly Ignite Economic Booms?

While spices catalyzed significant economic changes, they were not an isolated factor:

- Technological Advancements: Innovations in navigation and shipbuilding were equally critical to economic expansions.

- Political Stability: The ability to monopolize trade required political and military control.

- Diverse Commodities: Spices combined with other valuable goods like silk, gold, and textiles formed the backbone of ancient trade.

In many cases, spices triggered economic booms only when integrated within broader systems of trade and governance.

Conclusion

Spices were much more than tantalizing flavors—they were catalysts of economic dynamism that spanned continents and centuries. The pursuit of these precious commodities underpinned complex trade routes, empowered political entities, stimulated technological innovation, and became symbols of wealth and status. Although not the sole driver of ancient economic booms, spices ignited flames of prosperity and connections that shaped economic and cultural landscapes around the world.

From the caravanserais of Central Asia to the bustling ports of Venice and the exotic Maluku Islands, the history of spices is a vivid testament to the power of commerce and desire woven through human civilization’s fabric. Understanding this legacy enriches our grasp of global economic history and reminds us that even the smallest seeds can spark some of history's grandest narratives.

References:

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History (1st century CE)

- Chaudhuri, K.N., The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660–1760 (1978)

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L., Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 (1989)

- Pearson, M.N., The Indian Ocean (2003)

- Dalrymple, William, The Spice Route (2010)

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts