Which Pharaoh Shaped Egyptian Architecture Most

15 min read Explore the Pharaoh who most profoundly influenced the landscape of Egyptian architecture. (0 Reviews)

Which Pharaoh Shaped Egyptian Architecture Most

The ancient skyline of Egypt—marked by towering pyramids, monumental temples, and the silent gaze of stone pharaohs—tells a story of ambition, power, and enduring legacy. Of all the monarchs who reigned over the Nile Valley, some wielded architecture as their mightiest instrument of expression. But which pharaoh left the deepest, most transformative imprint on the landscape of Egyptian architecture? Journey through the sand-swept monuments and storied reigns as we discover who deserves this monumental status today.

The Unique Relationship Between Pharaohs and Architecture

Egyptian pharaohs were more than just rulers—they were divine intermediaries wielding absolute power. This status demanded physical manifestations through grand architectural feats. Royal tombs, shrines, and cities were more than political statements; they were spiritual investments in eternity.

From the earliest mastaba tombs to the sprawling temple complexes of the New Kingdom, architectural projects fulfilled religious, political, and economic roles. Nascent stone technology under Djoser, for example, set in motion Egypt’s signature building tradition. Meanwhile, complex temples doubled as economic powerhouses and propaganda tools, underscoring the pharaoh’s supreme authority. Whenever you gaze at an ancient Egyptian ruin, you’re seeing the blueprint of royal ambition etched in stone.

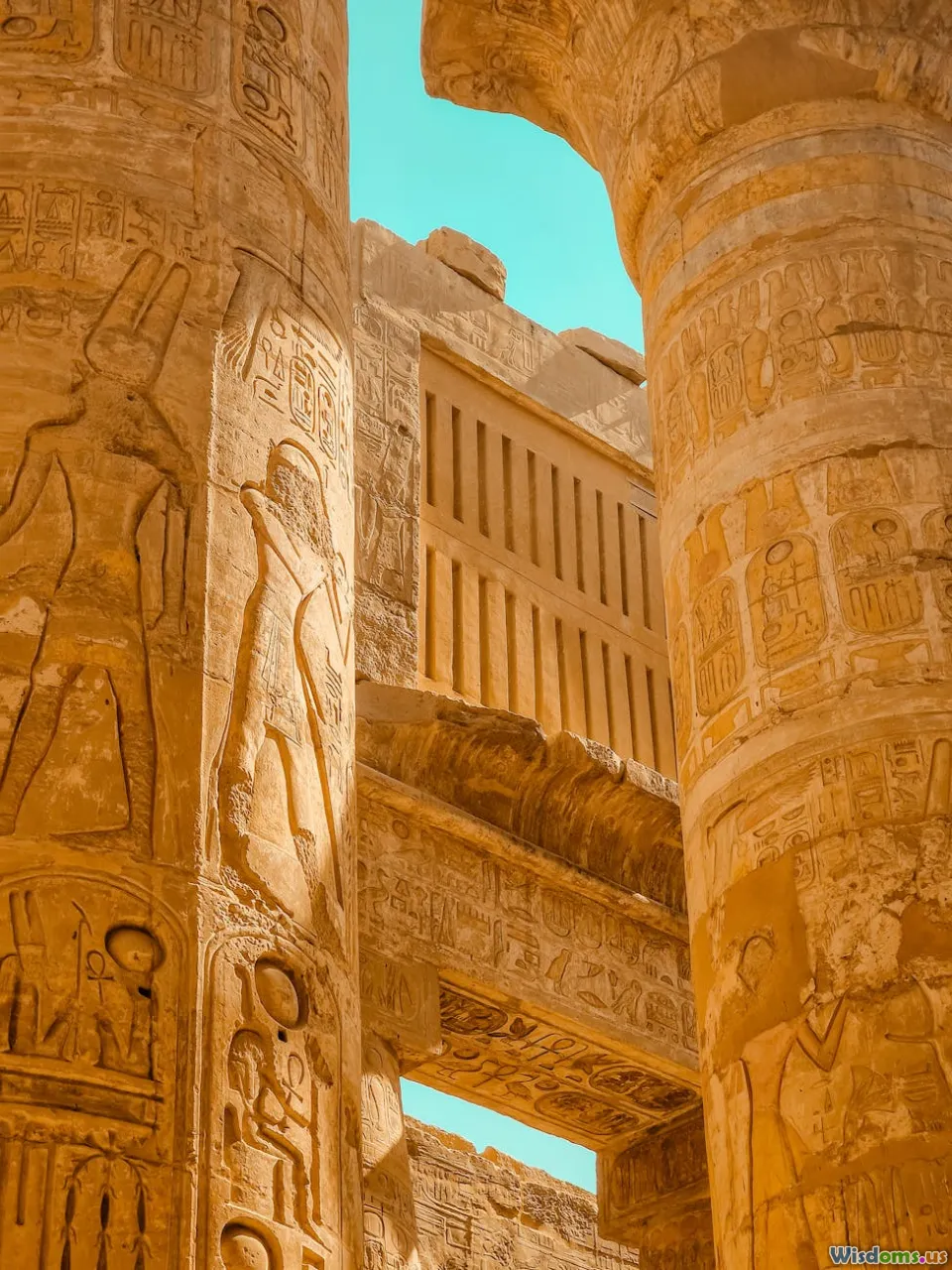

Hieroglyphs and the Built Environment

Inscribed walls—covered in elegant hieroglyphs and intricate scenes—chronicle not only the concerns of the afterlife but also the economic organization and social hierarchy that resting behind each stone. Pharaohs ensured their legacy by carving their names and deeds into almost every surface possible, ensuring generations would remember their architectural genius.

Djoser and the Dawn of Stone Architecture

When it comes to the roots of Egyptian monumental architecture, no discussion is complete without the illustrious Djoser of the Third Dynasty. Under his rule, Egypt transitioned from mudbrick construction to enduring stone—the architectural equivalent of shifting from wood to steel in modern times.

Djoser’s core achievement is the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, conceived by his remarkable vizier, Imhotep (often considered the world’s first architect). Before this breakthrough, royalty were laid to rest in simple, rectangular mastaba tombs. But Djoser’s Step Pyramid, standing at a height of over 60 meters, revolutionized burial architecture:

- First Monumental Stone Building: Previously unprecedented in scale and technical ambition.

- Multi-Functional Complex: Including temples and storerooms surrounding the pyramid, laying the template for funeral complexes to come.

This innovative leap inspired all future pyramids and marked the beginning of Egypt’s love affair with monumentality.

The Pyramid Age: Snefru and Khufu

Snefru's Architectural Revolution

Snefru, founder of the Fourth Dynasty, was the master innovator who perfected the art of pyramid-building. During his reign, he commissioned at least three major pyramids:

- The Bent Pyramid at Dahshur, with its unique angular shape.

- The Red Pyramid—the first true smooth-sided pyramid.

- A major pyramid at Meidum, originally built as a step pyramid and later transformed.

Snefru’s obsession with architectural progress paid off by refining techniques in stone-cutting, construction layout, and worker mobilization. He initiated the mass use of limestone casing stones, addressing earlier stability issues and creating Egypt’s classic geometric pyramid.

Khufu and the Great Pyramid

No discussion is complete without Khufu (Cheops in Greek), Snefru’s son, and builder of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Over 2.3 million stone blocks, some weighing more than 2 tons, were assembled to forge a tomb visible for miles. As the largest structure in the Giza pyramid trio, the Great Pyramid has become synonymous with both the glory and the mystery of ancient Egypt:

- Accurate Construction: Precise orientation to the cardinal points.

- Advanced Organization: Required resource mobilization on an unprecedented scale and workforce organization.

- Global Influence: Its grandeur fascinates engineers and archaeologists over millennia.

Both Snefru and Khufu set standards in the pyramid age, catalyzing Egypt’s most famous architectural legacy. Today, these structures symbolize Egypt’s Golden Age of pyramid construction and the absolute authority vested in the pharaoh.

The Transformation Beyond Pyramids

Eventually, the fervor for pyramid-building declined, but Egyptian architecture soared toward new forms. In the Middle and New Kingdoms, pharaohs channeled resources into sprawling temple complexes. These served as religions centers, local administrative hubs, and state economic engines.

Mortuary Temples and Karnak

The Mortuary Temple of Mentuhotep II at Deir el-Bahari, preceding the famed complex of Hatshepsut, illustrates this transition. The evolution continued at Karnak and Luxor, where successive pharaohs, from Sesostris I to the mighty pharaohs of the New Kingdom, demonstrated architectural ambition. But it’s during the 18th to 20th Dynasties that architecture reached its zenith.

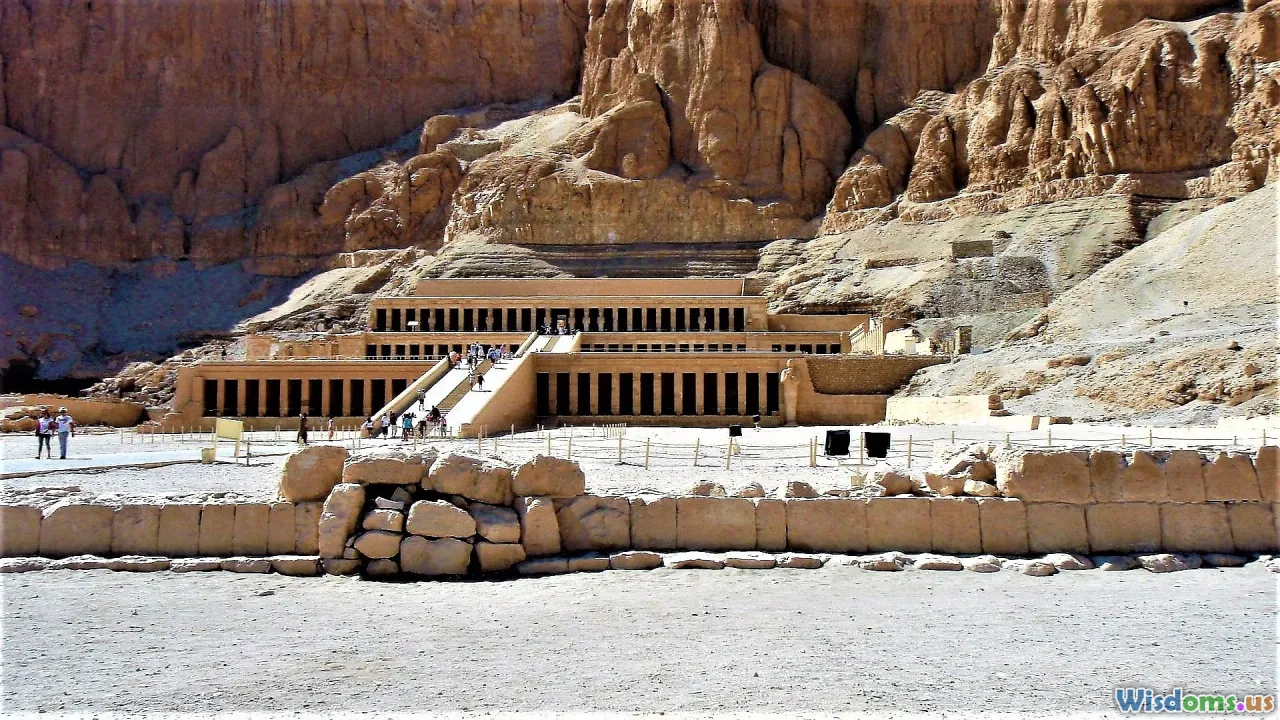

Hatshepsut: The Female Pharaoh and Her Architectural Vision

Among Egypt’s most remarkable rulers, Hatshepsut’s reign shines not only for its diplomatic successes but also for her architectural innovations. As one of history’s first great female leaders, she staked her legacy on building works to rival the mightiest pharaohs.

Her crowning architectural achievement is the mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari. Commanding the limestone cliffs west of Luxor, her temple was designed by Senenmut, her chief architect and advisor. Distinct features include:

- Three Terraced Levels: Each connected by ramps, integrating with the natural limestone cliff.

- Colonnaded Facades: Advanced columnar construction and open courts distinct from previous mortuary temples.

- Iconography: Relieve carvings documenting her divine birth and trading expeditions to Punt.

Hatshepsut’s architectural legacy set a precedent for future temple complexes and creatively adapted the built environment to the landscape, showcasing Egypt’s ability not only to monumentally build, but also harmoniously blend manmade and natural worlds.

Akhenaten: A Radical Shift in Design

Akhenaten’s reign marks one of the strangest, boldest experiments in Egyptian history—reflected directly in his architectural splendor. Breaking from polytheistic tradition, Akhenaten worshiped the sun disk Aten and uprooted Egypt’s religious center from Thebes to new grounds at Amarna.

Key aspects of Akhenaten’s architectural legacy:

- The City of Akhetaten (Modern Amarna): Purpose-built as a new religious locality, with open sun temples rather than dark sanctuaries.

- Architectural Style: Emphasis on openness, with offering tables exposed to sunlight.

- Relief Carvings: Radical break with artistic tradition—naturalistic depictions and loving familial scenes come to life on wall reliefs.

Although this architectural experiment faded after Akhenaten’s death and most of his innovations were systematically erased, the brief Amarna Age proved Egypt’s built environment was as dynamic as its political world. Today, excavation at Amarna continues to rewrite our understanding of royal self-representation.

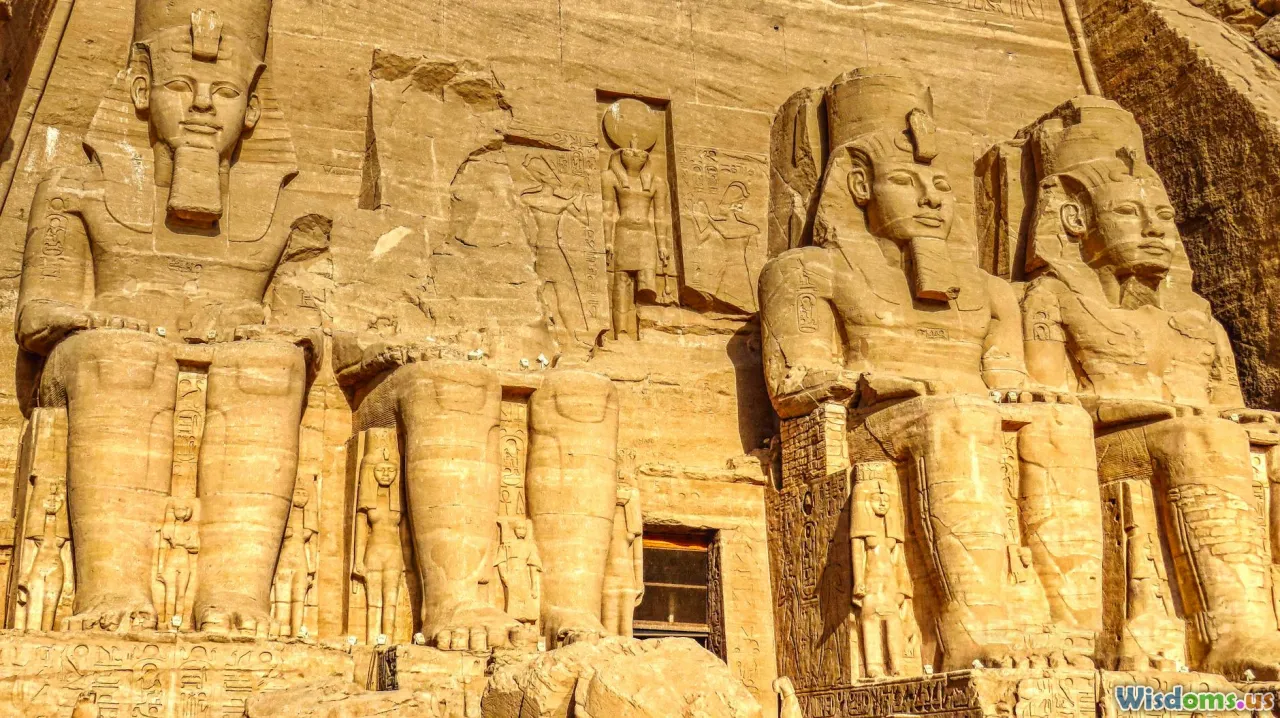

Ramses II: The Great Builder

If ancient Egypt had a builder-king who embodied monumentality, it was Ramses II—popularly known as "Ramses the Great." His reign, the second-longest in Egyptian history, was marked by massive building projects across Egypt and Nubia.

Abu Simbel: Carving God and Pharaoh from the Living Rock

Ramses’ most famous commission is the colossal temple complex at Abu Simbel, featuring four 20-meter tall statues of himself seated before the temple facade. Notable elements include:

- Sun Alignment: Twice a year, sunlight perfectly illuminates the sanctuary’s inner statues—a masterstroke of astronomical precision.

- Propagandistic Themes: Reliefs depicting the pharaoh’s military victories, especially at the Battle of Kadesh, fortify his image as warrior and benefactor.

- Engineering Challenges: Modern relocation of Abu Simbel due to the Aswan Dam in the 1960s is a testament to its enduring allure.

Beyond Abu Simbel: Mortuary Temples and More

Ramses built (or completed) more monuments than any other pharaoh, including the Ramesseum—the grand mortuary temple near Luxor, monumental pylons at Karnak, and dozens of temples across Egypt. Shrine inscriptions list his many expeditions, treaties, and accomplishments, reflecting his direct imprint on Egypt’s landscape.

Seti I and Temple Artistry

The father of Ramses II, Seti I also deserves mention for his architectural patronage, particularly the magnificent temple at Abydos. This complex, known for exquisite bas-reliefs and the famous king list, is a peak in Egyptian artistic achievement.

- Fine Carving: Seti’s temple boasts some of the most refined relief sculptures and hieroglyphic writing in ancient Egypt.

- Architectural Plan: Spatial innovations and decorated chapels distinguish the temple’s interior from prior designs.

His attention to detail and quality paved the way for the grandeur of his son Ramses II’s reign.

Comparing the Pharaohs: Lasting Impact on Egyptian Architecture

Compiling the achievements of these kings, a spectrum of Egyptian architectural evolution emerges:

- Djoser: Revolutionized permanent construction; established tradition of pyramid complexes.

- Snefru and Khufu: Perfected geometric pyramids, creating structures that shaped the identity of an entire civilization.

- Hatshepsut: Innovated harmonious design using natural landscapes; empowered a new approach to temple planning.

- Akhenaten: Demonstrated architecture’s adaptability to changes in belief and politics.

- Ramses II: Set the standard for grandiosity, scale, and propagandistic use of monuments.

While each contributed uniquely, it’s clear that Ramses II’s vast, still-visible legacy secures his position as "The Great Builder" in public imagination. But, without Djoser’s initial step, Khufu’s achievement, or Hatshepsut’s creativity, Egypt’s monumental tradition would have been unimaginably different.

Exploring Egypt’s Legacy Today

Contemporary visitors to Egypt can't help but marvel at the scale and symmetry of ancient architecture. For archaeologists, these monuments are ongoing puzzles, revealing clues about social organization, technological mastery, and the shifting ideals of power.

The rescue of Abu Simbel, threatened by rising waters from the Aswan Dam, is just one example of the global effort to preserve these treasures. Today, renewed interest in sustainable tourism and heritage management ensures that the legacies of Djoser, Khufu, Hatshepsut, Akhenaten, Ramses II, and other pharaohs will persist, inspiring generations to come.

To truly grasp which pharaoh shaped Egyptian architecture most is to appreciate the bucket chain of inventive ambition—a challenge passed from one visionary monarch to the next, leaving step pyramids, sun giants, and riverside sanctuaries across the timeless desert sands. From Saqqara's stacked layers to Abu Simbel's stone colossi, the stones themselves echo the immortality ancient Egypt so desperately sought.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts