Why Ride Sharing May Not Solve Commute Woes

34 min read Ride sharing promises smoother commutes, yet congestion, deadheading, and transit cannibalization persist. Explore data-driven reasons car-based platforms rarely reduce traffic, emissions, or travel times—and what works instead. (0 Reviews)

The pitch was irresistible: tap a button, share a ride, and watch traffic melt away. A decade into the ride-hailing revolution, many commuters have more options than ever—and yet the daily crawl often feels worse. If shared rides were supposed to unjam streets and shrink commutes, why hasn’t your trip to work gotten meaningfully faster?

The short answer is that the math of cities is stubborn. The longer answer is that ride sharing (in both its pooled and solo-hail forms) collides with geometry, economics, and human behavior. Understanding where it helps—and where it doesn’t—can save you time and guide better policy.

What We Mean by “Ride Sharing” (And Why Definitions Matter)

Before assessing impact, it’s crucial to distinguish between three related but different models:

- Ride-hailing: On-demand private rides via apps like UberX and Lyft. Occupancy often hovers around 1 to 1.3 passengers per trip in dense markets. These rides are convenient, but they do not inherently reduce cars on the road.

- Pooled rides: App-based shared trips (e.g., Uber Pool, Lyft Shared) that group strangers headed in roughly the same direction. In theory, two to three riders per vehicle spread the VMT (vehicle miles traveled) across multiple trips.

- Traditional carpool/vanpool: Co-workers or neighbors who pre-arrange shared rides, typically with consistent origins, schedules, and destinations; vanpools often carry 6–15 riders.

Why it matters: Most “ride sharing” headlines lump together ride-hailing (private) and pooling (shared). But a private ride is a taxi by another name. Pooling is the part meant to cut congestion—yet it’s a small slice. In many U.S. cities before the pandemic, pooled trips accounted for only 15–20% of app trips; post-pandemic, shared options have returned unevenly and with even lower adoption in many markets. The promise was founded on a behavior shift that hasn’t scaled.

Concrete example: If your 10-mile commute along a busy corridor averages 1.2 riders per vehicle using ride-hailing, you are not meaningfully beating congestion compared to solo driving. To lower traffic, average occupancies need to exceed two riders per vehicle—and do so consistently in peak hours and along predictable routes. App-based pooling has struggled to achieve this on typical weekdays outside a few dense corridors.

The Geometry Problem: Even Perfect Apps Can’t Bend Space

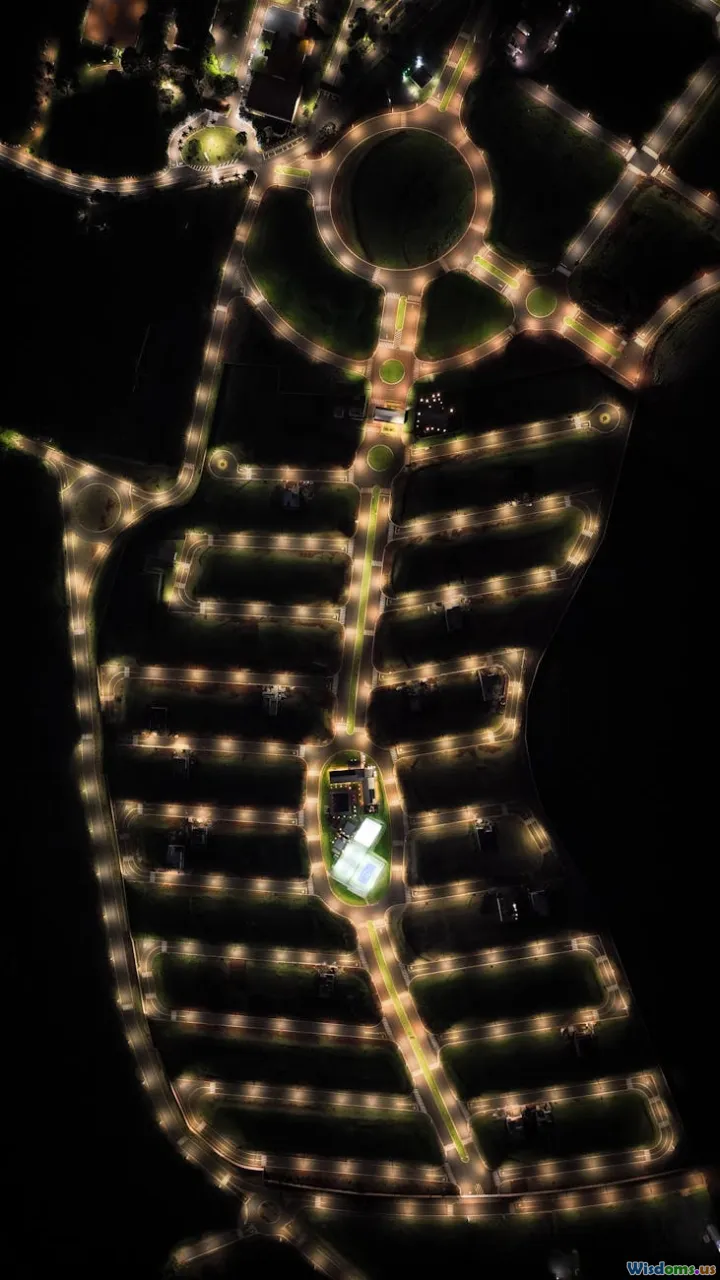

City streets have a fixed width and competing demands: cars, buses, bikes, pedestrians, deliveries, curb access. The key to moving more people in the same space is vehicle occupancy and right-of-way efficiency.

- A general-lane car corridor at 1.1–1.3 people per vehicle moves perhaps 1,500–2,000 people per lane per hour.

- A bus rapid transit (BRT) lane running 60-foot articulated buses every two minutes at 50–70 riders per bus can move 1,500–2,100 people per lane per hour—without the random stopping patterns of individual cars and pickups.

- A protected bike lane can deliver thousands of riders per lane per hour at peak in mature cycling cities with minimal curb interference.

Now add “pickup friction.” Shared trips require detours to find and collect riders. Even modest deviations compound on congested streets, diminishing the theoretical gains of higher occupancy. A three-stop pooled ride might add 10–15 minutes and several extra miles compared to each rider’s direct path.

This is the geometry problem: increasing occupancy by one or two riders doesn’t guarantee less congestion if the network absorbs extra curb events, detours, and empty repositioning. Space is finite; the more curb time and maneuvering ride sharing demands, the less throughput you get for everyone.

The Hidden Miles: Deadheading and Detours

Deadheading—the miles a ride-hail vehicle travels with no passenger—quietly erodes the efficiency story. Studies in multiple cities have put deadheading rates for ride-hailing between roughly 30% and 40% of total driver miles. The breakdown:

- Repositioning to high-demand areas

- Cruising while awaiting a hail

- Driving to a pickup (especially when riders are on opposite sides of a congested corridor)

Detours compound the problem. Even pooled trips often detour several minutes for each additional pickup or drop-off. In practice, the “shared” portion covers only a segment of the journey, while the system accumulates extra miles from pickup choreographies.

Example: In a dense downtown, suppose a driver covers 15 miles during a two-hour peak window, but only 9 miles carry paying passengers. The 6 empty miles add traffic without moving any commuter. At scale, thousands of such partial miles transform into visible congestion in choke points and around popular pick-up zones.

Crucially, deadheading is not just a driver behavior; it’s an algorithmic outcome. Dispatch systems try to minimize wait times to keep customers satisfied, but shorter waits generally mean more vehicles circulating. The faster the promised pickup, the more likely there’s a car cruising nearby—even if no passenger is inside.

Congestion Where It Hurts: Curb Chaos and Hot Spots

Several urban studies have documented the localized impact of ride-hail activity on congestion. While overall traffic may rise modestly, the distribution is uneven: certain blocks become much worse.

- Downtown cores: High job density, nightlife, and events cluster pickups. Double-parking during peak periods creates rolling bottlenecks.

- Entertainment districts: Short, frequent trips with high turnover saturate the curb and introduce constant merging and stopping.

- Transit hubs: When riders substitute short ride-hails for walking or bus transfers around train stations, curb space clogs at precisely the places that need throughput.

Evidence snapshots:

- In San Francisco, analyses of mid-2010s traffic patterns attributed a large share of increased congestion to ride-hail activity, particularly in the northeast quadrant where jobs and nightlife concentrate. Hot spots correlated with curb pick-ups, not just through traffic.

- In New York City’s core, pre-pandemic data showed that ride-hail vehicles frequently clustered in Manhattan below 60th Street, contributing to slower crosstown speeds around evening peaks.

- Chicago’s central area observed notable increases in ride-hail trips during peak periods, helping explain degraded bus speeds on key corridors.

The operational takeaway: It’s not only how many rides happen, but where and when they cluster. Without managed curbs, designated staging, and time-of-day pricing, even small increases in vehicles can produce outsized delays on critical blocks.

The Cannibalization Problem: When “Options” Steal Riders From Transit

Ride-hailing became the easy mid-distance option for many commuters, often at the expense of public transit. Surveys from multiple U.S. metros in the late 2010s found that a sizeable share of ride-hail users would otherwise have walked, biked, taken the bus or train, or not made the trip at all.

What that means:

- If riders trade a bus ride for a solo or lightly pooled car trip, the system moves fewer people per lane and per operator-hour. Bus speeds also fall when cars clog the lane, degrading transit reliability and pushing more riders toward cars—a feedback loop.

- Off-peak transit substitution isn’t as damaging; buses have spare capacity late at night. But when substitution occurs in peak hours on busy corridors, the collective loss is significant.

Example: A 6-mile urban commute previously served by a frequent bus—averaging 35 riders per bus—will carry fewer people if even 10–15% of riders swap to ride-hail. As bus speeds fall due to increased curb conflicts, agencies reduce frequency to preserve on-time performance, making the bus less attractive and reinforcing shift to cars. Over time, marginal riders leave transit, but streets get slower for everyone.

To be fair, ride-hail can play a constructive role as a first/last-mile connector to high-capacity transit, especially where sidewalks are incomplete or safety is a concern. But that works best when it’s explicitly integrated (e.g., discounts to train stations during off-peak, or geofenced zones that nudge rides to transit rather than replacing it end-to-end).

Equity, Access, and the Worker Puzzle

Shared mobility platforms promised access for communities underserviced by legacy transit. Reality is mixed:

- Accessibility: Wheelchair-accessible vehicles are still limited in many markets. Wait times can be long and coverage spotty. Incomplete curb ramps, broken sidewalks, and limited driver training compound the barrier for riders with disabilities.

- Geographic coverage: Suburban and exurban areas have fewer drivers and longer deadheading distances, raising prices and making reliable pooling rare.

- Pricing: Dynamic pricing often peaks when riders have no alternatives—late nights, storms, event nights. That can be regressive for service workers and low-income commuters with non-standard hours.

- Labor economics: Driver earnings depend on demand density, platform policies, fuel prices, and vehicle costs. Efforts to increase occupancy (e.g., pooling) can sometimes reduce per-trip pay if compensation models aren’t updated for multi-rider stops. Policy changes—minimum pay standards, benefits—aim to address gaps but also affect fleet size and availability.

In short, ride sharing can increase mobility for some underserved users but is not an equity silver bullet. A resilient system still requires safe sidewalks, reliable transit, fair wages, and accessible vehicles.

Climate Math: Cleaner Cars Help, But Empty Miles Still Count

The climate case for ride sharing rests on three levers: occupancy, electrification, and trip substitution. Here’s the nuance:

- Occupancy: A pooled ride with two or more riders can reduce per-person emissions compared with solo driving—if detours are minimal. But if deadheading and detours add 40–60% extra miles, the gains shrink quickly.

- Electrification: Electric ride-hail fleets cut tailpipe emissions. Yet electricity grid mix, battery manufacturing, and upstream emissions still matter. Moreover, empty EV miles are still miles—where congestion and road wear are concerned.

- Trip substitution: If ride-hail replaces walking, cycling, or transit, total emissions can rise. If it replaces a dirty, congested solo drive, emissions can fall. The direction depends on local mode shifts.

Practical estimate: Suppose two co-workers share a pooled EV for a 10-mile trip, with 2 extra miles of detour and 3 deadhead miles. That’s 15 EV miles total. Per person, that’s 7.5 EV miles instead of 10 ICE miles each—likely an emissions win, especially with a cleaner grid. But the same trip in a bus operating at median load would still be more energy-efficient per passenger-mile while using less road space. As ridership scales, buses and trains win the climate geometry more often than two-person pooled cars.

Bottom line: Electrification helps, but congestion is a physical problem. A street full of EVs is still a busy street.

Why Pooling Hasn’t Scaled: The Reliability Trade-off

Pooling seems elegant in presentations; it is messy in real life.

- Matching complexity: To keep wait times low, platforms need many compatible riders originating near each other within a narrow window and heading along roughly the same path. Suburban dispersion breaks the model; even urban riders often diverge after a few miles.

- Reliability penalty: Every added pickup risks a cancellation, an extra wait, or an unexpected detour. Commuters value predictability; a pooled ride that unpredictably adds 10 minutes is a deal-breaker.

- Trust and comfort: Sharing a vehicle with strangers remains a barrier for a slice of riders, particularly late at night or during flu seasons.

- Pandemic whiplash: Pooling paused or shrank during COVID-19. Some riders never returned to it, and some cities changed curb operations, reducing the friction tolerance for multi-stop rides.

The outcome: Pooling stays niche without powerful incentives or structural changes—like dedicated pickup areas, priority lanes, or employer-backed vanpools that guarantee seats and schedules. The market has spoken: when reliability and comfort clash with marginal cost savings, reliability wins.

Where Ride Sharing Does Work for Commuters

There are use cases where ride sharing is a genuinely smart commute choice:

- First/last-mile to high-capacity transit: If you’re 2–3 miles from a frequent rail or BRT line, a short ride-hail or pooled trip can shave 20 minutes off transfers and make transit viable.

- Late-night or very early shifts: When buses run infrequently, a shared ride gives safe, time-certain access. These trips don’t cannibalize peak transit capacity and can improve job access.

- Park-and-ride connectors: Pair a carpool or ride-hail to a suburban park-and-ride with high-frequency express service into the city. This limits the city driving segment and leverages high throughput in the core.

- Occasional backup: When you miss a train or the bus is severely delayed, ride-hail is a useful Plan B rather than a default mode.

- Vanpools for clustered workplaces: Where employers cluster (e.g., hospitals, distribution centers), vanpools with guaranteed seats and cost-sharing can match or beat solo commuting in time and price.

These are narrow but powerful niches: ride sharing complements, rather than replaces, high-capacity modes.

A Step-by-Step Method to Choose the Best Commute for You

If your current commute feels inefficient, use this simple audit to decide when, if ever, ride sharing makes sense.

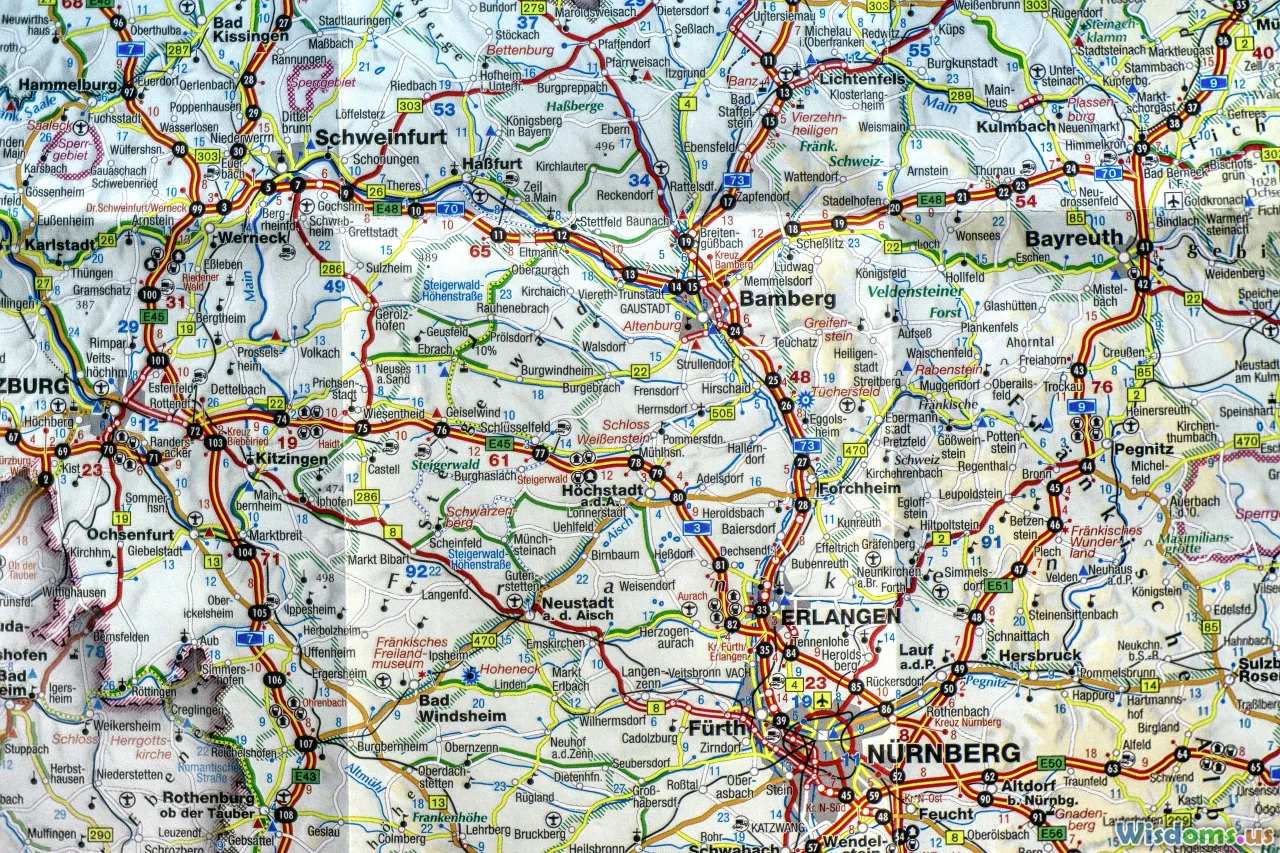

- Map your options door-to-door

- List modes: walk/bike, bus, rail, BRT, ride-hail (solo), pooled, carpool, vanpool, park-and-ride combinations.

- Note real-world schedules and typical wait times, not just theoretical headways.

- Calculate total time variability

- For each option, estimate typical time and worst-case time in peak traffic.

- Add transfer, pickup, and wait times. Pay special attention to curb pickup reliability.

- Compute true monthly cost

- Ride-hail: tally base fares, surge premiums, tips, and fees. Multiply by commute days.

- Driving: include gas/electricity, parking, depreciation, insurance, and tolls.

- Transit: consider passes and employer subsidies.

- Evaluate predictability vs. flexibility

- If your work hours vary, on-demand options gain value.

- If punctuality is critical, ask if a pooled ride’s detours are acceptable versus a reliable train/bus.

- Stress-test a hybrid

- Example: Bike 1 mile to BRT, then ride-hail from the station only on rainy days or late nights.

- Use ride-hail as a targeted connector, not a daily crutch.

- Pilot for two weeks

- Try your best two options for a full work cycle. Track actual times and costs.

- Make your choice based on data, not hope.

A typical outcome: Many commuters discover a transit-plus-occasional-ride-hail combo delivers the best balance of cost, reliability, and stress reduction.

What Cities Can Do Today: A Practical Toolkit

If the goal is faster, fairer commutes, cities have levers that out-perform hoping that pooling will scale spontaneously.

-

Prioritize street space for people-moving capacity

- Install and enforce dedicated bus lanes on key corridors; pair with transit signal priority to lift bus speeds by 10–25%.

- Build protected bike and micromobility lanes to shift short trips out of cars.

-

Price congestion fairly

- Congestion pricing in dense cores nudges discretionary trips out of peak periods and funds transit. Time-of-day curb pricing can reduce pickup chaos.

- Consider per-trip fees that favor pooled rides during peak hours—but pair with bus lane enforcement so buses still win on predictability.

-

Manage the curb

- Create designated pickup/drop-off zones on side streets to keep general lanes flowing.

- Use sensors or digital permits to prevent double-parking, and enforce actively during peaks.

-

Make transit irresistibly reliable

- Frequency is freedom: aim for 10-minute or better headways on trunk lines.

- Real-time information and fare integration with ride-hail for first/last-mile.

-

Demand data and transparency

- Require anonymized, aggregated trip data from platforms to identify hot spots, assess VMT, and plan curb allocations.

-

Support equitable access

- Incentivize wheelchair-accessible vehicles and driver training; require response time standards for accessible trips.

- Offer targeted subsidies or late-night ride programs where transit is sparse, tied to essential-worker shifts.

-

Pilot microtransit carefully

- On-demand shuttles sound appealing but often carry few riders at high subsidy per trip. Define success metrics upfront (cost per rider, average occupancy, wait times), and sunset underperforming pilots.

What Platforms and Employers Can Do

Ride-hail companies and employers hold powerful levers to improve commutes without worsening traffic.

For platforms:

- Incentivize true pooling

- Offer larger discounts for rides that actually match and share distance, not just attempted pools.

- Penalize unnecessary cancellations that break shared trips; reward riders who accept small detours.

- Integrate with transit in-app

- Default to showing transit plus short connector rides as the top option when it’s faster door-to-door.

- Sell bundled passes with transit agencies; offer guaranteed transfer protection for missed connections.

- Prioritize curb stewardship

- Geofence no-stopping zones, direct riders to legal pickup bays, and share heat maps with cities for dynamic curb allocation.

- Electrify smartly

- Facilitate charging access and promote high-utilization EV fleets for urban cores where congestion pricing and air quality goals overlap.

For employers:

- Offer commuter benefits

- Pre-tax transit, employer-funded transit passes, or shuttle services between rail stations and campuses.

- Support flexible schedules and remote/hybrid work

- Spread demand out of peak periods; compressed workweeks can cut commute days entirely.

- Seed vanpools

- Subsidize or coordinate vanpools for clustered employees on similar schedules. Guarantee ride home in emergencies.

- Align site planning with mobility

- Choose offices near frequent transit, provide secure bike parking and showers, and price parking to reflect its true cost.

Myths vs. Realities

-

Myth: “More ride sharing equals less traffic.”

- Reality: Without high occupancy and managed curbs, ride-hail adds VMT via deadheading and detours, often worsening congestion where it matters most.

-

Myth: “Pooling can replace buses.”

- Reality: Pooled cars rarely sustain the throughput of a single bus lane with frequent service. Transit carries more people per unit of space.

-

Myth: “Electrifying ride-hail solves the commute problem.”

- Reality: EVs cut emissions, not road space. Without mode shift or pricing reform, EVs still clog lanes.

-

Myth: “Microtransit will fix suburban commutes.”

- Reality: Many pilots show high costs per rider and low occupancy. Targeted, fixed-route express or vanpools often perform better.

-

Myth: “If we just improve algorithms, pooling will flourish.”

- Reality: Human behavior (reliability preference) and urban geometry impose limits that software alone can’t erase.

A Practical Comparison: Five Commute Scenarios

- Dense urban corridor with frequent bus/BRT

- Best bet: Bus/BRT with transit priority; use ride-hail only for first/last-mile in bad weather.

- Why: Capacity and predictability beat pooled detour risk. Curb conflicts hurt pooled trips more.

- Suburban home to downtown rail station (3 miles), then 12-mile rail

- Best bet: Bike or short ride-hail to station; rail for the trunk; occasional ride-hail on late returns.

- Why: Minimizes city driving, leverages high-capacity rail, saves money and time.

- Late-night hospital shift with unreliable hourly bus

- Best bet: Ride-hail or carpool for the late-night legs; explore an employer vanpool if colleagues share shifts.

- Why: Safety and time certainty; minimal congestion externality at 2 a.m.

- Crosstown trip with two school drop-offs in rush hour

- Best bet: If school is along the route of a frequent bus/tram, split the trip: walk/bus for school, then ride-hail for the last hop; otherwise, consider carpooling with another family to reduce repeat trips.

- Why: Reduces duplicative miles while retaining child drop-off needs.

- Industrial park commute with scattered origins, poor sidewalks

- Best bet: Employer-backed vanpool with pre-set stops; ride-hail as a backup.

- Why: Vanpools solve the dispersion problem with guaranteed seats and shared cost.

The Policy Math: Pricing, Space, and Time

The dominant variables that shape commutes are not app features; they are pricing, space allocation, and time reliability.

-

Price signals need to reflect true costs

- Congestion pricing or cordon fees better align private vehicle trips with their externalities. Pair revenues with improved transit.

- Time-of-day TNC fees can nudge trips out of the worst peak windows or into shared modes.

-

Space allocation determines speed

- Dedicated lanes for high-capacity modes produce outsized gains in person-throughput and reliability. Prioritize them on corridors with proven demand.

-

Time reliability drives mode choice

- Travelers choose predictability over small cost differences. Policies that make transit—and safe cycling—reliably faster win riders even without rock-bottom fares.

When cities adopt these levers, ride sharing finds its healthiest niche: as a connector, not a replacement, for the backbone modes.

Designing for Fewer Trips, Not Just Faster Ones

The ultimate commute solution is fewer commute miles.

- Land use: Mixed-use zoning and infill development reduce average trip lengths and enable walking or short rides.

- Remote/hybrid work: Even one fewer commute day per week cuts congestion noticeably on some corridors.

- Staggered schedules: Schools, offices, and logistics centers that spread start times flatten the peak.

These are not quick fixes, but they multiply the benefits of every transportation investment. When there are fewer trips to begin with, the limitations of ride sharing matter less.

Actionable Tips You Can Use This Week

- Buy a monthly transit pass if you ride at least three round-trips per week; the marginal cost of occasional ride-hail becomes easier to justify when transit is prepaid.

- Identify your three worst bottlenecks and avoid them entirely—even if it means a slightly longer path on a dedicated transit or bike corridor.

- Join or create a vanpool if five or more colleagues live within a 20-minute radius; rotate driving and split costs.

- Use ride-hail as a “gap filler” for late-night or weather-impacted days, not the default.

- Ask your employer for pre-tax transit benefits and flexible start times; these are low-cost asks with outsized impact.

- For safety and predictability, pre-select known pickup spots (e.g., a side-street loading zone), and build five minutes into your plan for staging.

The Pragmatic Path Forward

Ride sharing is neither villain nor savior. It is a powerful mobility tool that thrives in particular niches: as a connector to high-capacity transit, a late-night safety net, a vanpool backbone for clustered jobs, or an occasional relief valve. Expecting it to “solve” the commute is asking the wrong question.

If you need a faster, less stressful commute, think in layers. Start with the modes that move the most people in the least space—trains, buses in their own lanes, protected cycling—then layer on targeted ride-hail for the gaps. If you write policy, align prices with impacts, build reliable right-of-way for high-capacity modes, and manage the curb with intention. If you run a company, give your workers the benefits and schedules that shift them away from the peak car crush.

The streets we want are the result of the choices we make about space, time, and price—not the apps on our phones. Use ride sharing smartly, not blindly, and you’ll find it helps your commute in the ways it’s actually good at—without waiting for it to do the one thing it never could: move more people through a city than the city itself will allow.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts