Why Time Dilation Is More Than Science Fiction The Physics Behind It

18 min read Explore the real physics behind time dilation and its fascinating impact beyond science fiction. (0 Reviews)

Why Time Dilation Is More Than Science Fiction: The Physics Behind It

Imagine sending a message to your future self by simply traveling faster or venturing close to a massive black hole. While this sounds like the stuff of mind-bending science fiction, it is, in fact, the groundwork of modern physics. Time dilation — the phenomenon where time itself moves at different rates depending on speed or gravity — sits at the very heart of our understanding of the universe. But what brings this fantastical-sounding concept squarely into the realm of real science? Let’s journey into the evidence, misconceptions, practical uses, and philosophical implications that make time dilation one of the most fascinating effects in physics.

The Foundations: Einstein's Twin Pillars of Time Dilation

Time dilation enters physics through two revolutionary ideas proposed by Albert Einstein in the early 20th century: Special Relativity and General Relativity. Where classical Newtonian mechanics assumed time was universal and absolute, Einstein posited a radically different view: the passage of time is not fixed — it can stretch or shrink, depending on certain key factors.

- Special Relativity (1905): This theory illustrated that time contracts and space compresses for individuals traveling at high velocities, especially as they approach the speed of light.

- General Relativity (1915): Einstein expanded his view, revealing that strong gravitational fields curve both space and time, leading to gravitational time dilation — time runs slower closer to massive objects.

Example: The famous "twin paradox" (described in detail later) is rooted in Special Relativity, while the operation of GPS satellites owes corrections to the effects predicted by both.

Einstein’s predictions, initially met with skepticism, have since been confirmed time and again through experiment and observation.

Speed and Time: Special Relativity’s Role

One of the most mind-boggling consequences of Special Relativity appears when objects approach the speed of light (roughly 299,792 km/s). According to Einstein’s equations, as an object's velocity increases, its experience of time slows down relative to that of a stationary observer.

The Twin Paradox: A Concrete Example

Suppose two identical twins share a birthday and live together on Earth. One twin then sets off on a high-speed journey to a distant star aboard a hypothetical spacecraft capable of reaching speeds close to that of light. The other stays home. When the traveling twin returns, fewer years have passed for them, making them biologically younger than their Earth-bound sibling.

-

Formula:

The mathematical relationship is: ( t' = \frac{t}{\sqrt{1 - v^2/c^2}} )

where ( t' ) is the time elapsed for the traveling twin, ( t ) is for the stationary twin, ( v ) is velocity, and ( c ) is the speed of light.

-

Real Example:

In 1971, physicists Joseph Hafele and Richard Keating flew atomic clocks onboard commercial airliners while identical clocks remained on the ground. The clocks on planes recorded less time, aligning almost perfectly with Einstein’s predictions.

Practical Tip: Don’t Dismiss It as Just Theory

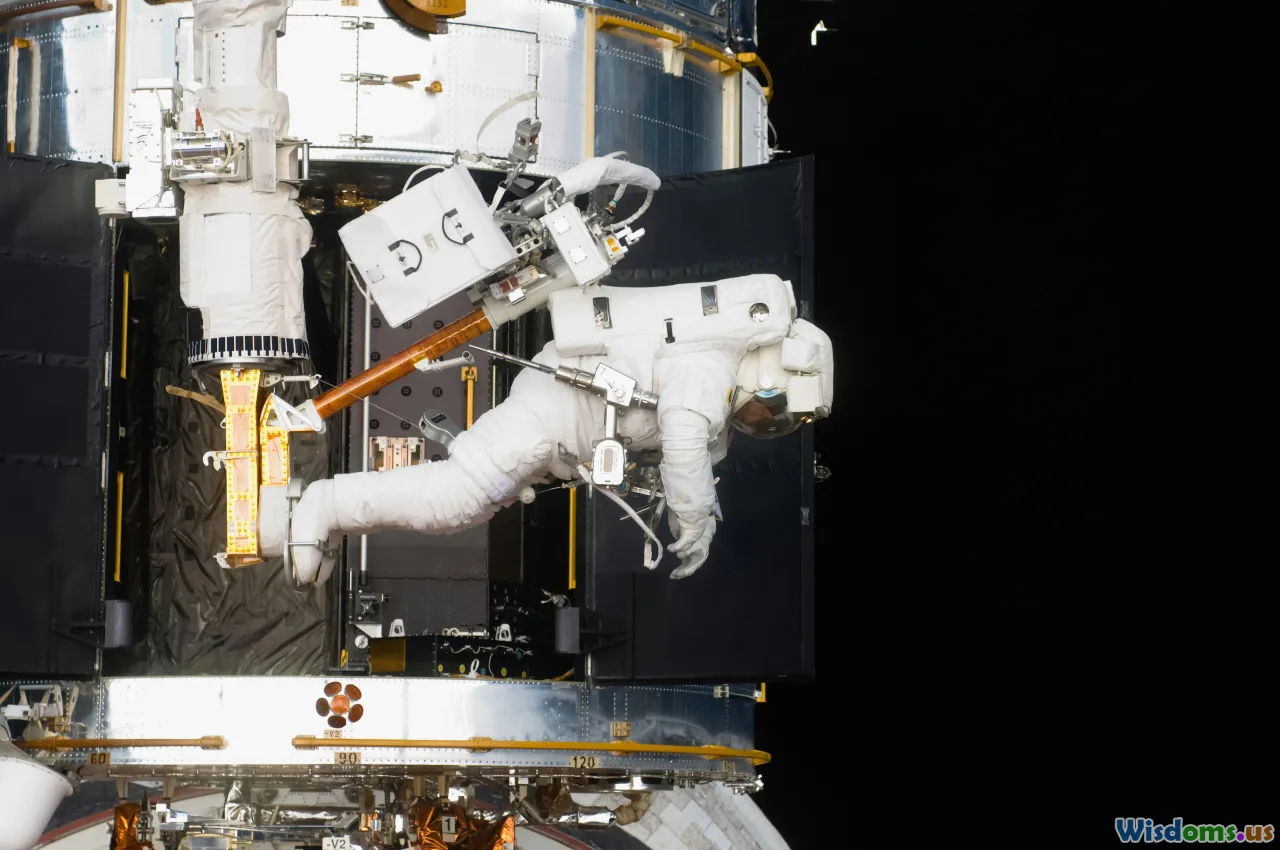

Every time an astronaut spends extended periods on the International Space Station — orbiting Earth at around 28,000 km/h — their biological clock ticks slightly slower than ours. Over six months, the difference is only milliseconds, but measurable nonetheless.

Gravity and the Flow of Time: General Relativity’s Insights

Speed isn’t the only factor affecting time. Gravity, or more specifically the strength of gravitational fields, also bends the river of time. General Relativity reframes gravity not as a force but as the warping of spacetime itself; like weight on a trampoline, massive objects such as stars, planets, and black holes stretch and curve the fabric on which time runs.

Gravitational Time Dilation: Standing on Everest versus Sea Level

If you stand at the foot of Mount Everest and your friend stands atop it, both of you will age at slightly different rates because the person lower down is deeper within Earth’s gravitational field. The difference is infinitesimal — around 2.45 microseconds per year — but real, measurable, and even crucial in precision sciences.

Extreme Example: Near a Black Hole

The movie Interstellar dramatizes this with scientific accuracy. A team lands on a planet near a supermassive black hole — for every hour spent there, seven years pass on Earth. Though exaggerated for cinematic purposes, the principle is valid. The closer you are to tremendous gravity, the slower your clock.

Testing Time Dilation: More Than a Thought Experiment

Time dilation is not merely a beautiful mathematical flower or science fiction prop; it is proven science, validated by rigorous observation.

Atomic Clock Experiments: Hafele-Keating and Beyond

-

Airliners and Atomic Clocks: In the 1971 Hafele-Keating experiment, four cesium atomic clocks circled the globe aboard commercial jets. Upon returning, discrepancies with stationary ground clocks matched the effects expected from both special and general relativity.

-

Satellites: GPS satellites, orbiting 20,200 km above Earth but also zipping in their orbit, are prime examples. Their on-board clocks gain about 45 microseconds per day due to weaker gravity (general relativity) but lose about 7 microseconds due to their speed (special relativity). Failing to adjust for this would render GPS navigation useless.

Particle Accelerators: Aging Subatomic Particles

In 1941, physicist Bruno Rossi discovered that fast-moving muons (elementary particles) produced in Earth's upper atmosphere survive much longer before decaying than muons produced at rest. Their high speeds slowed their "clocks," allowing them to reach ground level. Modern accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider depend on relativistic equations to predict experimental results.

Tip for the Sceptical: Look at Everyday Technology

Take note when using your smartphone for directions, transferring money, or watching satellite TV. All these services rely on technology that must account for time dilation daily, or else they veer off course and malfunction in hours.

The Role of Time Dilation in Modern Technology

Time dilation isn’t just an oddity known only to theoretical physicists; it shapes the engineering behind essential systems that touch our lives.

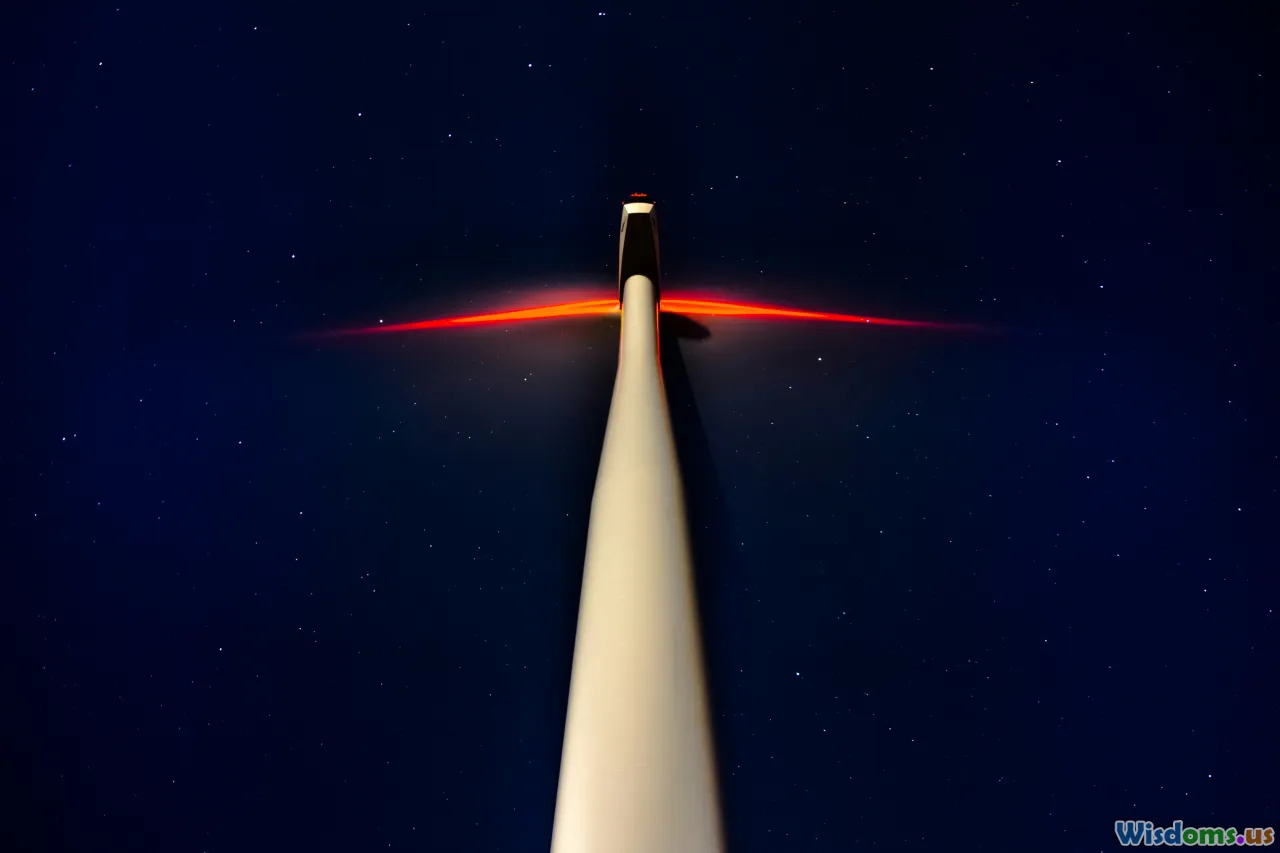

Global Positioning System (GPS)

Arguably, GPS systems are the most alive with relativistic ingenuity. The 32-satellite network beams signals down to Earth so your phone or car can determine precise location. For accuracy at the meter level, atomic clocks on satellites must account for relativity:

- Special Relativity: Satellites move at about 14,000 km/h, causing their clocks to lag behind ground-based ones.

- General Relativity: Positioned further from Earth’s center, they experience weaker gravity and therefore, according to general relativity, their clocks run faster.

The net effect: satellite clocks are adjusted by about 38 microseconds per day — critical, since a mere 20-30 nanoseconds of unsynchronized time can translate to kilometer-scale errors.

Data Communication and Networking

Relativistic time corrections also factor in long-range communication systems that synchronize signals at millisecond accuracy across the planet. Without relativistic corrections, international finance, military navigation, geodesy, and even high-speed trading would be unreliable.

Hard Science in Action: The Lifespan of Muons

Muons stream through the atmosphere every second, generated as cosmic rays strike air molecules. At their typical speeds (98-99% speed of light), they have enough measured lifetime to reach the surface, contrary to what would be expected if time were absolute. Accelerator scientists have used this effect to calibrate detectors and design experiments probing the smallest building blocks of matter.

Science Fiction vs. Scientific Fact: Tropes and Truths

Hollywood and sci-fi novels love to riff on time dilation, often exaggerating or misapplying the effect for dramatic purposes.

Movie Tropes: Fun but Flawed

- Approaching the Speed of Light: Films may show astronauts returning home after decades away, to find the world radically changed, invoking the reality of time dilation. While the mechanics are true, achieving such speeds with current technology is inconceivable due to energy requirements—hence the allure in fiction.

- Warp Drives and Wormholes: Sci-fi routinely blends relativity with hypothetical shortcuts through space, such as wormholes. While Einstein’s theories allow for warping space-time — enabling potential time travel under very specific, theoretical conditions — no physical evidence for traversable wormholes exists.

- Aging Backwards: Some stories creatively invert time, but relativity never rolls personal time backwards; it only slows its march relative to others.

Separating Science from Fiction

Much of popular culture’s misunderstanding comes from treating time travel as a broken clock rather than a consequence of nature’s rules. Time dilation does enable "forward time travel" for high-speed travelers or those reliant on intense gravity. But backward travel, time paradoxes, and changing futures, as seen in entertainment, remain speculative with no substantiated physics.

Everyday Clocks — Subtle Effects Down on Earth

Does time dilation matter down here, on our everyday planet? Absolutely, though the effects are usually too slight to notice unaided.

High-Precision Clocks Detect the Unseen

Atomic clocks in metrology labs in Boulder, Colorado, and Paris, France, routinely register the minuscule difference in the passage of time due to elevation differences (gravitational redshift). In 2010, University of Colorado scientists measured a clock sitting just 30 centimeters higher ticking slightly faster than one lower down — a difference in elevation smaller than a desk height.

Airplanes, Trains, and You

The movie "Passengers" may show decades zipping by in minutes, but as far as your next cross-country flight is concerned, the effects are minimal: roughly a few dozen nanoseconds will separate you from someone sitting at home. For precise scientific work — in calibrating networks or time stamps — even those micro-effects matter.

Philosophical Ramifications: Rethinking Time

Time dilation prompts deep questions — philosophical ones that reach beyond numbers and measurements.

Is Time an Illusion?

Einstein famously said, "People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion." Time dilation’s verified existence means that “now” is not a fixed universal moment. Different observers, moving at varying velocities or standing in differently curved spacetimes, experience reality in a personalized way. This challenges our age-old assumptions about objective passage and forces us to reconsider ideas of destiny, memory, and personal history.

The Human Perception of Time

If every ticking second is relative, then experiences, histories, and even futures hinge upon your particular vantage point in the universe. Scientists, artists, and philosophers continually grapple with what this means for the human experience. Could our subjective time, already influenced by emotion and attention, actually have a parallel in the cosmic dance of fundamental forces?

Embracing Relativity: The Future of Time Dilation in Science

The march toward exploring time dilation isn't over; technologies and theoretical advances suggest even broader and more profound applications. Ideas like interstellar hibernation, quantum time sensors, and relativistic communication for missions to Mars and beyond will push us deeper into understanding and using time’s flexibility.

Interstellar Explorers

As space agencies ponder missions to neighboring stars, accounting for both velocity- and gravity-based time effects becomes essential. American physicist Kip Thorne and others envision future spacecraft housing ever more sensitive on-board clocks, able to maneuver through gravity wells and relativistic speeds with minimal error margins.

Medical and Biological Insights

One research frontier investigates whether relativistic environments (e.g., long orbital journeys) might impact biological processes or even slow aging-related diseases. If time's passage truly bends for those in orbit, could a tiny medical benefit be coaxed for long-term astronavigation?

Building the Next-Gen Experiments

Fundamental physics ventures such as the Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space (ACES) onboard the International Space Station aim to improve clock synchronization across the solar system, testing relativity’s predictions over unprecedented distances.

In summary, time dilation is no fringe effect or exaggerated sci-fi device — it’s a deep property of our very existence, woven into the technologies and philosophical questions that shape the modern era. With every new discovery, we edge closer to a world where controlling and understanding time is as tangible as launching satellites or exploring other galaxies. Next time your smartphone directs you down a busy avenue or you watch distant stars twinkle, remember: the universe is always subtly reshaping time, frame by frame.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts