Five Olmec Legends That Still Influence Art Today

13 min read Explore five iconic Olmec legends and their enduring impact on contemporary art forms worldwide. (0 Reviews)

Five Olmec Legends That Still Influence Art Today

The lush jungles and riverbanks of Mesoamerica held one of the greatest mysteries in ancient history—the Olmec civilization. Flourishing from around 1500 BCE to 400 BCE, the Olmec are often revered as the 'Mother Culture' of Middle America. While their massive stone heads and extraordinary jade carvings continue to awe the modern world, their legends linger mysteriously in today's art. From figurative sculpture to vibrant murals and contemporary installations, these primal stories still pulse at the heart of creative inspiration.

Let’s explore five foundational Olmec legends—and see how they resurface as symbols and stories across today’s artistic movements.

The Legend of the Jaguar People

The most iconic figure in Olmec lore is the "were-jaguar," a shape-shifting entity blending human features with those of the fearsome jungle cat. To the Olmec, the jaguar was the embodiment of raw power—a godlike creature driving storms, fertility, and leadership. According to legend, the first rulers traced their lineage to unions between a jaguar spirit and a noblewoman.

Cultural Symbolism

Olmec artisans immortalized this myth in hundreds of jade and clay figurines—each with oversized almond eyes, snarling mouths, and fanged grins. The half-human, half-jaguar motif represented both physical might and spiritual transcendence. Art historians point to the were-jaguar mask motifs carved into ceremonial altars and reliefs, prefiguring later Mesoamerican gods like Tezcatlipoca.

Influence on Modern Art

The were-jaguar legacy roars forth in contemporary sculpture. In Mexico City, artists like Javier Marín blend human anatomy with feline musculature, harnessing the primal tension inherent in transformation. The fusion reflects identity complexities in a postcolonial world. For painters and tattoo artists worldwide, jaguar iconography signals a connection to intuitive energy and ancestral heritage—a narrative both personal and political.

How Artists Can Channel This Legend

- Experiment with Hybridity: Combine animal and human elements in portraits or masks.

- Embody Power: Use the jaguar's stance and gaze to evoke strength in figures.

- Explore Metamorphosis: Depict transformation as a metaphor for personal or societal change.

The Tale of the World Tree

Many Olmec stories revolve around the axis mundi—the World Tree that bridges the underworld, earth, and sky. In ceremonies and sculpture, the tree emerges not just as a botanical presence, but as a divine portal topped by the ceiba, a towering tropical giant.

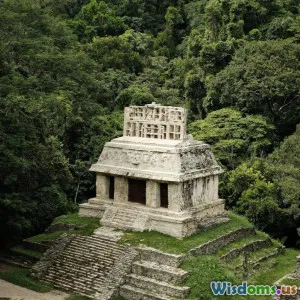

Mythic Roots and Artistic Representation

Olmec stelae (upright carved stones) often show rulers emerging from caves or the mouths of serpents at the base of a massive cross-shaped tree. This is a graphic translation of cosmovision: the belief that realms are interconnected. Carvings from sites like La Venta (900–400 BCE) feature stylized branches teeming with supernatural beings, suggesting access to otherworldly knowledge.

Resonance in Contemporary Art

The motif of the World Tree has found new life in the hands of Chicana muralists, environmental sculptors, and Indigenous illustrators. Contemporary murals, such as those by Mexican-American artist Margarita Cabrera, integrate tree trunks swirling upward to the heavens, signifying persistence and connection. In eco-art installations, artists create ‘living totems’ that convey the vulnerabilities and interdependence of modern ecosystems.

Tips for Integrating the World Tree in Your Art

- Layer the Tree’s Symbolism: Use root, trunk, and branch imagery to represent life’s stages or personal growth.

- Bridge Worlds: Pair organic forms with geometric designs to visualize the link between the mundane and the spiritual.

- Invite Collaboration: Explore textile or mixed-media projects that engage communities in telling their own stories of interconnectedness.

The Serpent as a Bridge Between Worlds

Serpents slithered fluidly through Olmec tales, not as villains but as magical intermediaries, potent guides through shadowy underworlds and into the light. The most notable is the Feathered Serpent—a precursor to Mesoamerica’s Quetzalcoatl—an emblem of rain, fertility, and creative dynamism.

Ancient Depictions and Symbolic Nuances

On altar carvings and pottery shards, the Olmec present serpents undulating between dimensions, coiling above and below human figures. The motifs sometimes take on stylized forms, their feathers merging with sinuous bodies, encircling ceremonial scenes. Archeologists at San Lorenzo discovered a stone monument featuring two intertwined serpents whose bodies arc around a ruler—a visual of blessing and transformation.

Modern Echoes

In modern art and architecture, serpents are frequently rendered in mosaic, mural, or kinetic sculpture. Architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez designed the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City with serpentine water features, representing historical continuity. In the United States, Southwest and Indigenous artists fold rattlesnake and water-serpent themes into contemporary jewelry and prints—symbols of wisdom, cyclicality, and creative flow.

Artistic Applications

- Play With Movement: Use winding, repeating lines to infuse art with energy and dynamism.

- Combine Old and New: Reference ancient Olmec curls and motifs in digital or urban art.

- Link Opposites: Juxtapose bright and dark palettes, or soft and hard textures, as a nod to the serpent’s role as an intermediary.

The Child of Maize: Birth, Death, and Regeneration

Maize—the foundation of Mesoamerican agriculture—holds a central place in Olmec mythology. Tales describe the appearance of the Maize Child, a miraculous offspring sprouting from the sacred earth, feeding the people and dictating the cycle of life. Olmec heads with childlike features celebrate not merely innocence but the generative power of corn, the sustainer of civilizations.

Archaeological Evidence and Symbolism

Exaggerated ‘baby face’ sculptures, with smooth chubby cheeks and plump lips, have been recovered from burial sites and altars. These may represent both newborn gods and the first humans shaped by maize dough—the same fruit of the earth and spirit described in later Nahua and Maya creation myths. Such figures were often broken during maize festivals, a ritual return to the womb, symbolizing birth, sacrifice, and hope.

Artistic Rebirths in the Modern Era

Today's Latino and Indigenous artists evoke the Maize Child through pop surrealism and social narrative. The cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz’s “El Niño del Maíz” series recasts the maize child as a superhero battling threats to traditional agriculture. Meanwhile, heirloom-seed conservationists commission murals blending human and maize forms, weaving narratives of resilience and ancestry.

How Contemporary Artists Can Draw from This Legend

- Celebrate Regeneration: Depict themes of growth, change, and rebirth through cycles of sowing and harvest.

- Explore Dualities: Use the baby face to express both vulnerability and creative potential.

- Advocate Through Art: Raise awareness of indigenous agricultural knowledge, food sovereignty, or genetic diversity via portraits or installations.

The Rainbow Serpent and the Waters of Creation

Another enduring Olmec legend invokes the wind-blown Rainbow Serpent—a deity coiling between clouds, summoning storms and rivers with a vibrant arc. Seen as the bringer of rain, this entity fostered fertility in fields and hearts alike. The legend embodies both joy (abundance) and the threat of floods or droughts, inviting reverence for nature’s immense, unpredictable power.

Traces in Olmec Art

MVibrant murals unearthed from Olmec ceremonial sites show snakes adorned with swirling, multicolored motifs arching over water scenes. These depictions foreshadow later Aztec and Maya rain gods adorned in turquoise and ochre, alluding to the shimmer of a freshly fallen rain. The Rainbow Serpent bridges the wild unpredictability of weather with the grounded cycles of sowing and harvest.

Modern Iterations and Influences

In Latin American muralism, the Rainbow Serpent reappears—sometimes almost literally, painted in radiant bands above river subcultures or environmental protests. In Australian Aboriginal art (echoing a different but conceptually related Rainbow Serpent), sweeping color forms articulate the guardianship of water sources.

Installation artists have built inflatable snakes stretching between rooftops, each scale decorated with textile patterns to express collective memory and current climate anxieties. The symbolism extends to urban graffiti: twisting water dragons that dance above drought-prone city blocks, celebrating resilience and the eternal promise of renewal.

Actionable Ways to Integrate the Rainbow Serpent

- Work With Color Theory: Blend iridescent hues and gradation to convey movement and transformation.

- Highlight Water Stories: Use the serpent and rainbow as motifs in art advocating for clean water access and conservation.

- Collaborate Across Cultures: Explore comparative mythology with artists from distant regions who envision their own "serpent" traditions.

The Olmec left no written books, yet their legends live on in stone, pigment, and the hands of today’s creators. By tapping into these primal myths—the shapeshifting were-jaguar, the world tree, the boundary-blurring serpent, the ever-renewing maize child, and the rainbow-born water dragon—artists find both ancestral roots and new branches for expression. Every brushstroke or carefully carved line connects the ancient and the now, echoing a legacy that will continue to shape our collective imagination.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts