Why ARM Cortex M Is Transforming Embedded Systems Programming

34 min read How ARM Cortex M microcontrollers reshape embedded programming with deterministic real-time performance, ultra-low power, rich peripherals, CMSIS ecosystem, and secure toolchains across STM32, nRF52, and Kinetis platforms. (0 Reviews)

The last decade quietly rewrote the rules for embedded development. Products that once needed custom ASIC blocks or bulky 16/32-bit processors now run on postage‑stamp microcontrollers sipping microwatts. If you trace that change, you’ll find one recurring ingredient: the ARM Cortex‑M family. More than just a CPU core, Cortex‑M created a stable architectural target, a tooling standard, and a shared performance envelope that let hardware and software teams move faster, cheaper, and with fewer surprises. This is why Cortex‑M isn’t just popular—it’s transforming how embedded systems get built.

What Changed: From 8-bit Habits to 32-bit Momentum

For years, 8‑bit and 16‑bit MCUs dominated low‑cost embedded systems. Developers optimized around tight RAM, small Flash, and instruction sets that made C compilers sweat. Cortex‑M disrupted that equilibrium by bringing 32‑bit compute, modern compilers, and deterministic interrupt handling to price points many teams once reserved for 8‑bit.

Key shifts that explain the momentum:

- Cost parity with capability: You can buy a Cortex‑M0+ device for well under a dollar in volume. That budget used to limit teams to 8‑bit cores with awkward toolchains and limited performance. Now, 32‑bit math, larger address spaces, and high‑level C/C++ are the default.

- Determinism and real‑time predictability: Cortex‑M’s NVIC (Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller), tail‑chaining, and late‑arrival behavior give consistent, analyzable interrupt latencies. Real‑time behavior that once required careful hand‑coded assembly is now baked into the architecture.

- Ecosystem standardization: CMSIS (Cortex Microcontroller Software Interface Standard) harmonized low‑level access across vendors. It made switching from, say, ST to NXP far less painful and enabled an explosion of middleware, RTOS ports, and examples.

- Performance per watt: Low‑power design was not an afterthought. M0+ can hit “tens of microamps per MHz” in many families, and higher‑end M4/M7 parts add sleep modes, DMA, and event routing to keep the CPU idle.

The practical outcome: teams spend their time on product features rather than wrestling the MCU.

Know Your Cores: M0+ to M55 (and Why It Matters)

Cortex‑M is a family, not a single core. Picking the right one saves BOM cost, reduces power, and simplifies code. A quick, practical tour:

- Cortex‑M0/M0+ (Armv6‑M): The smallest/lowest power. Excellent for simple sensors, appliance controls, and battery-powered nodes. M0+ refines the pipeline for lower power and adds features like single‑cycle I/O on some implementations. Typical flash sizes: 16–256 KB; RAM: 2–64 KB. Examples: Microchip SAM D10/D21 (M0+), NXP KL03, ST STM32G0.

- Cortex‑M3 (Armv7‑M): General-purpose workhorse with better performance and richer instruction set (e.g., hardware divide). Great for moderate complexity, industrial I/O, and control systems. Examples: older STM32F1/F2, NXP LPC17xx.

- Cortex‑M4/M4F (Armv7‑M + DSP + optional FPU): Adds single‑cycle MAC, saturating arithmetic, and optional single-precision FPU. Ideal for motor control, audio processing, and sensor fusion. Examples: STM32F3/F4/G4, NXP Kinetis K64, Nordic nRF52 (M4F with BLE/2.4 GHz radio).

- Cortex‑M7 (Armv7‑M, high performance): Dual‑issue, deeper pipeline, caches, and optional single- or double‑precision FPU. Targets advanced control, networking stacks, and real-time signal processing. Often comes with TCM (tightly coupled memory) for deterministic execution. Examples: STM32F7/H7, NXP i.MX RT crossover MCUs (600+ MHz).

- Cortex‑M23/M33 (Armv8‑M with TrustZone‑M): Security‑forward variants. M33 typically includes DSP and FPU options while enabling secure/non‑secure partitions in hardware (TrustZone‑M). Examples: NXP LPC55S6x, ST STM32L5/U5, Renesas RA series.

- Cortex‑M55 (Armv8.1‑M with Helium): Adds M‑Profile Vector Extension (MVE/Helium), bringing 128‑bit vector operations to MCU‑class parts for efficient DSP and ML. Often paired with Arm Ethos‑U NPUs on some devices.

Rule of thumb:

- Choose M0+ when “years on a coin cell” and price are critical, with modest math needs.

- Choose M4F when you need DSP and floating point for control loops or sensor fusion.

- Choose M7 when you need cache+TCM, multi‑layer bus, and heavy real‑time workloads.

- Choose M33/M23 for secure IoT with TrustZone‑M.

- Consider M55 for edge ML and advanced DSP without a separate DSP chip.

Determinism, NVIC, and Real-Time Behavior You Can Reason About

Real‑time systems live or die by predictability. Cortex‑M treats interrupt handling as a first‑class citizen:

- NVIC with priorities: Up to 240 external interrupts, each with programmable priorities (typically 4–8 bits implemented). This lets you guarantee that critical ISRs preempt less critical ones.

- Tail‑chaining: When one interrupt finishes and another is pending, the core can jump directly without fully restoring and re‑stacking registers. This trims interrupt-to-interrupt latency down to only a handful of cycles in many cases.

- Late arrival: If a higher‑priority interrupt arrives during the entry of a lower‑priority ISR, the core can switch to the higher priority before fully entering the lower one.

- Automatic stacking: On exception entry, general-purpose registers are pushed automatically. You don’t need prologue/epilogue assembly hand‑crafting for basic ISR context management.

- SysTick: A standardized 24‑bit timer for system ticks, profiling, and periodic events; every Cortex‑M has it.

In practical terms, you can design a motor‑control loop on an M4F with a 20 kHz update rate, run a CAN bus stack, and still keep interrupt jitter limited because the architecture enforces consistent behavior across vendors.

Performance per Watt: Sleep Well, Wake Fast

Efficiency isn’t just “low current.” It’s how quickly you can get work done and go back to sleep. Cortex‑M supports this pattern via:

- WFI/WFE instructions: Wait For Interrupt/Event lets the core drop into sleep while peripherals or events keep running.

- Multiple sleep states: Vendor‑specific modes (Sleep, Stop, Standby, Shutdown) balance retention versus wake time. Wake latencies are often in microseconds.

- DMA and event systems: Route data from ADC->memory->peripheral without waking the CPU. Lower energy because the core stays in WFI.

- Low‑power peripherals: I2C, RTC, and watchdog often operate in deep sleep, enabling “always on” timekeeping sensor nodes.

Typical figures vary wildly by process technology and vendor, but “tens of microamps per MHz” in run mode for M0+ and “hundreds of microamps per MHz” for performance M7 parts are common. The trick is to optimize duty cycle, not only instantaneous current.

Example: A BLE sensor node using a Nordic nRF52840 (Cortex‑M4F) can sample an accelerometer via SPI + DMA at 100 Hz, buffer data, wake the radio for a connection interval, compute a simple FFT in bursts, and then sleep—achieving multi‑month or multi‑year life on a coin cell depending on connection intervals and sensor duty cycles.

Memory and Bus Architecture: Speed Where It Counts

Embedded performance is often about memory: where code runs, where data lives, and how the bus arbitrates access.

- Flash and ART/accelerators: Vendors add prefetch and caches so code can execute from Flash with minimal stalls. Zero‑wait Flash is rare at high clocks, so prefetch buffers matter.

- SRAM tiers: “Tightly Coupled Memory” (TCM) on M7 provides deterministic, single‑cycle access for critical code (ITCM) and data (DTCM). Put interrupt handlers, control loops, and hot data here.

- I/D caches: On M7 and some M33, separate instruction/data caches reduce latency when executing from Flash or external QSPI.

- Multi‑layer AHB bus matrices: High‑end MCUs offer separate masters (CPU, DMA, Ethernet MAC, SDMMC) that can access SRAM and peripherals concurrently. Careful placement of buffers avoids contention.

- External memory: Some parts support QSPI/OctoSPI and SDRAM. For OTA firmware and large assets, execute‑in‑place (XIP) from QSPI is common; keep tight loops in SRAM/TCM for determinism.

Concrete tip: On STM32H7, place your USB and Ethernet DMA buffers in AXI SRAM; keep ISR code in ITCM; keep filter coefficients and stack in DTCM. This minimizes bus fights with Flash and peripheral traffic.

Peripherals That Compress Schedules

Cortex‑M success isn’t only the core—it’s the rich peripheral sets across vendors that solve real problems:

- Timers galore: Advanced timers with dead‑time insertion and complementary outputs drive half‑bridges for motor control (e.g., STM32G4). High‑resolution modes and hardware synchronization simplify FOC (field‑oriented control).

- ADCs and DACs: 12‑ to 16‑bit ADCs with multi‑channel scan, oversampling, and hardware triggers. Some families offer sigma‑delta ADCs; others include op‑amps/comparators on‑chip.

- Communication: I2C, SPI, UART, CAN/CAN FD, USB FS/HS (often with integrated PHY for FS), Ethernet MAC with DMA, SDMMC/SDIO, QSPI for external Flash.

- Audio/voice: PDM microphone interfaces, SAI/I2S, and DFSDM (digital filters for sigma‑delta modulators) on certain STM32 devices.

- Math accelerators: CORDIC (for fast trig), FMAC (for MAC pipelines), CRC engines; hardware AES/SHA/TRNG in security‑oriented parts.

Example: A brushless motor controller on STM32G4 uses ADC injected conversions triggered by timer edges, DMA to collect currents, and a CORDIC peripheral for fast Park/Clarke transforms. The CPU computes PI loops while peripherals align sampling with PWM edges—deterministic and low jitter.

Tooling That Feels Modern: CMSIS, Packs, and IDEs

One of Cortex‑M’s biggest gifts is consistency. CMSIS defines names for registers, exception numbers, and core features. This lets libraries and tools “just work” across silicon vendors.

- CMSIS‑Core: Standard headers for SysTick, NVIC, and core registers.

- CMSIS‑DSP and CMSIS‑NN: Optimized math and neural network kernels tuned for M‑profile cores.

- CMSIS‑Driver and Packs: Vendor‑agnostic peripheral driver interfaces and installable device support packages.

- IDE/toolchains: Keil MDK, IAR EWARM, and open GCC/Clang toolchains with CMake or vendor IDEs (STM32CubeIDE, NXP MCUXpresso, Renesas e2 studio). PlatformIO brings a modern cross‑vendor workflow.

- Debug probes: Segger J‑Link, ST‑Link, CMSIS‑DAP compatible probes; SWD (2‑pin) reduces pin cost vs JTAG.

If you’re starting from scratch, a practical stack might be: GCC + CMake + OpenOCD/J‑Link + VS Code + CMSIS + your vendor’s HAL/LL library. It’s portable and long‑term maintainable.

RTOS and Middleware: Batteries Included

Cortex‑M popularized small RTOS usage: FreeRTOS, Zephyr, RTX, and others run everywhere. Why it matters:

- Portability: CMSIS‑RTOS2 provides a common API layer across RTOS choices.

- Deterministic primitives: Mutexes, semaphores, event flags, and tickless idle let you scale from bare‑metal to multi‑task designs with minimal power penalty.

- Middleware: TCP/IP stacks, USB device/host, BLE stacks, and file systems are preintegrated for many families (e.g., STM32Cube middleware, NXP MCUXpresso SDK, Nordic nRF Connect SDK built on Zephyr).

Tip: Treat the RTOS as a scheduling and I/O plumbing tool, not as a license to write blocking code everywhere. Use DMA + interrupts to keep task CPU time bounded.

Security You Can Actually Ship: MPU, TrustZone‑M, and Crypto

Security is now table stakes. Cortex‑M helps at multiple layers:

- MPU (Memory Protection Unit): Enforce read/write/execute permissions for code and data regions. Typical MCUs implement 8 or more regions with subregion controls—enough to sandbox stacks and guard against errant pointers.

- TrustZone‑M (Armv8‑M): Partition the system into Secure and Non‑Secure worlds with hardware gates. A Secure Attribution Unit (SAU) and Implementation Defined Attribution Unit (IDAU) define boundaries, with secure veneers for controlled calls. This underpins secure boot and key storage.

- Hardware crypto: AES, SHA, ECC accelerators, and true random number generators. Some families add secure key storage backed by PUFs (Physically Unclonable Functions) or one‑time programmable fuses.

- Reference firmware: Trusted Firmware‑M (TF‑M) provides PSA Certified reference services (secure storage, crypto, attestation) on M23/M33.

Practical pattern: Store firmware images in external QSPI, verify a signed manifest in Secure world at boot (TrustZone‑M), then jump to Non‑Secure app. Use MPU to protect task stacks and code sections even within Non‑Secure.

DSP and TinyML: Doing More on the Edge

The line between “MCU” and “signal processor” keeps blurring:

- CMSIS‑DSP: FFTs, filters, matrix ops with hand‑tuned assembly paths for M4/M7. You can implement a 256‑point FFT well under a millisecond on a 100‑200 MHz M4F.

- CMSIS‑NN and TensorFlow Lite Micro: Quantized 8‑bit kernels fit into tens of kilobytes and run in real‑time for basic keyword spotting or anomaly detection.

- Helium (M55): M‑Profile Vector Extension accelerates DSP and ML with 128‑bit vector registers and predication—bringing SIMD to MCUs. Combined with Ethos‑U NPUs, inference per milliwatt jumps.

Example: A vibration sensor uses a 1D CNN to classify bearing defects. On an M4F at 80–120 MHz, a 10–20 kB model runs in tens of milliseconds per window using CMSIS‑NN. With an M55 + Helium, you may see several‑fold speedups at similar power, enabling higher sampling rates or more classes.

Migration Playbook: From 8/16-bit to Cortex‑M Without Drama

Moving a mature 8‑bit codebase to Cortex‑M isn’t scary if you respect a few patterns:

- Pick the right core and memory. If your old part had 32 KB Flash/2 KB RAM at 16 MHz, consider a Cortex‑M0+ with 64–128 KB Flash and 8–16 KB RAM. Leave headroom for drivers and a basic RTOS.

- Map timing‑critical ISRs first. Port the ISRs and timers you know must be deterministic. Use NVIC priorities wisely—e.g., give a 10 kHz control loop a higher priority than UART and GUI events.

- Replace bit‑banging with peripherals. Move SPI/I2C/UART to hardware drivers with DMA. Use timer capture/compare for protocol edges.

- Use CMSIS and vendor HAL/LL. Even if you ultimately go bare‑metal, start with HAL to get working quickly, then peel off to LL/bare‑metal in hot paths.

- Add MPU early. Catch wild pointers in development by protecting null page, code sections, and stacks. This saves weeks of debugging later.

- Build test harnesses. With GCC/Clang and CMake, you can unit test non‑hardware code on your PC; use a hardware‑in‑the‑loop setup for drivers.

Expect a productivity bump simply from better compilers and debuggers, even before you leverage DMA and RTOS features.

Hands-On: A Few Bare-Metal Building Blocks

Here are compact, portable snippets that lean on CMSIS rather than vendor-specific HAL, so they work across Cortex‑M families.

- SysTick tick and a simple ISR:

#include "cmsis_gcc.h"

#include "core_cm4.h" // or core_cm0plus.h, etc.

volatile uint32_t g_ticks = 0;

void SysTick_Handler(void) {

g_ticks++;

}

static inline void delay_ms(uint32_t ms) {

uint32_t start = g_ticks;

while ((g_ticks - start) < ms) {

__WFI(); // sleep until next tick or interrupt

}

}

int main(void) {

SystemCoreClockUpdate();

SysTick_Config(SystemCoreClock / 1000); // 1 kHz

// Toggle a GPIO here (left to vendor)

while (1) {

// do work...

delay_ms(10);

}

}

- Measuring cycles with DWT on M3/M4/M7:

static inline void dwt_init(void) {

CoreDebug->DEMCR |= CoreDebug_DEMCR_TRCENA_Msk;

DWT->CYCCNT = 0;

DWT->CTRL |= DWT_CTRL_CYCCNTENA_Msk;

}

uint32_t measure_fn(void (*fn)(void)) {

uint32_t start, end;

start = DWT->CYCCNT;

fn();

end = DWT->CYCCNT;

return end - start;

}

- ADC->DMA streaming concept (pseudocode using CMSIS names):

void adc_dma_setup(void) {

// Configure ADC in continuous or trigger mode

// Configure DMA: peripheral-to-memory, circular buffer

// Enable DMA interrupt for half/full transfer

}

void DMA_IRQHandler(void) {

// Process half-buffer while DMA fills the other half

}

These patterns scale: You can swap HAL/LL calls for register writes, but the architectural pieces (SysTick, DWT, NVIC) stay constant.

Debug and Trace That Find Real Bugs

Cortex‑M debug features are a practical superpower:

- SWD: Two‑pin debug with breakpoints, memory access, and flash programming. Saves pins on dense layouts.

- ITM + SWO: Real‑time printf‑style logging without halting the core. ITM stimulus ports can stream trace messages at megabits per second.

- DWT: Watchpoints, cycle counters, and PC sampling help capture hard‑to‑reproduce timing bugs.

- ETM/ETB (on higher‑end parts): Instruction trace for reconstructing exact execution paths—indispensable for deep RTOS issues or code coverage.

A practical workflow: Use ITM to log state transitions and sensor samples during long field tests; add a DWT cycle counter around critical sections; reserve ETM for those once‑a‑quarter bugs where you must replay the past.

A Clearer Comparison: Cortex‑M vs Alternatives

- Against 8/16‑bit MCUs (AVR, PIC, MSP430): Cortex‑M wins on toolchain maturity, 32‑bit math, code density (Thumb), and available middleware. Power and cost now overlap; the 8‑bit case shines mainly for ultra‑ultra‑low power niche parts or when legacy code locks you in.

- Against RISC‑V MCUs: RISC‑V is advancing quickly with credible low‑power and mid‑range parts and an open ISA story. Today, Cortex‑M still enjoys a broader commercial middleware and debug ecosystem, especially for DSP/ML and secure firmware. Many teams prototype on both; for time‑to‑market, Cortex‑M often has the edge, while RISC‑V can be compelling where openness and custom extensions matter.

- Against Wi‑Fi SoCs (ESP32, etc.): If you need Wi‑Fi plus application CPU, an ESP32‑class SoC can be great. For ultra‑low power sensing, tight real‑time control, or long battery life, a dedicated Cortex‑M MCU (often paired with a low‑duty radio like BLE) typically wins on energy and determinism.

Always prototype with your workload; datasheet MHz doesn’t predict end‑to‑end latency when caches, buses, and DMA are in play.

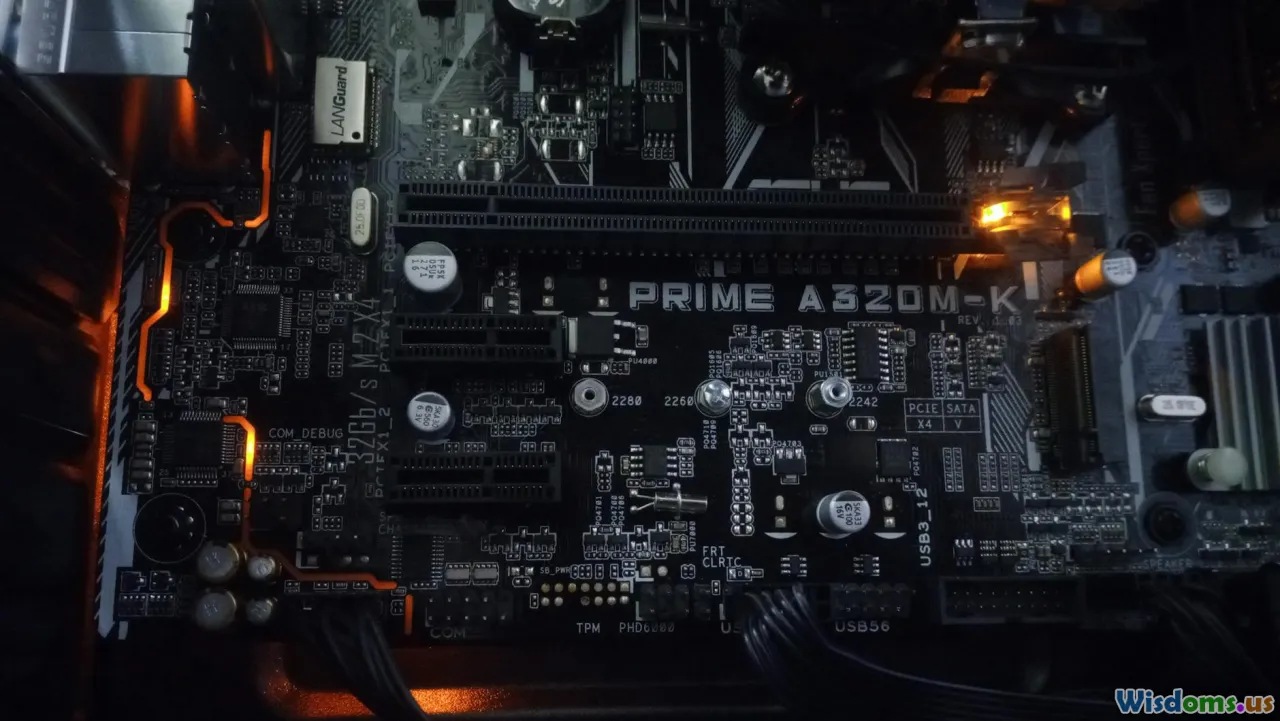

Selecting Silicon: Vendor Landscapes and Differentiators

While the core is standardized, families differ a lot in peripherals, analog, and software kits:

- STMicroelectronics STM32: Huge breadth (G0/L0/L4/U5/F4/H7/G4). Strong CubeMX/CubeIDE tooling, rich middleware. G4 for motor control; H7 for high‑end with Ethernet/USB HS; L4/U5 for low power.

- NXP LPC and i.MX RT: LPC55Sxx (M33 with TrustZone‑M, good security); i.MX RT “crossover” M7 at 500–600 MHz with large SRAM and external QSPI XIP—great for GUI/audio.

- Nordic nRF52/nRF53: BLE/2.4 GHz radios with M4/M33 application cores and excellent RF stacks and power profiles.

- Renesas RA series (M23/M33/M4/M7): Strong security options, CAN FD, and industrial grade, with e2 studio support.

- Microchip SAM D/E (M0+/M4): Easy Arduino/Atmel Studio roots (SAMD21 popular in maker space), solid low‑power.

- TI MSP432 (legacy) and SimpleLink: Legacy M4F parts; newer SimpleLink devices bundle radios.

- GigaDevice GD32: STM32‑like pinouts with competitive pricing; check ecosystem fit.

Choose by peripherals first (timers, ADC resolution, comms), then power/performance, then security and toolchain support. Evaluate long‑term availability and vendor roadmaps.

Pricing, Availability, and Design-for-Supply

Cortex‑M’s ubiquity helps with sourcing, but shortages happen. Practical steps:

- Dual‑source footprints: Pick pin‑compatible families (e.g., STM32G4 vs F3 pin‑compat) or keep alt options in the schematic.

- Avoid edge SKUs: Extremely new or niche parts are often supply‑constrained. Prefer mid‑range, high‑volume models.

- External Flash flexibility: If using QSPI for assets/OTA, keep options for multiple Flash vendors.

- Cost bands: Sub‑$1 (M0+ basic), $2–$6 mainstream M3/M4, $8–$20 high‑end M7 with Ethernet/USB HS. Prices vary with package and on‑chip memory.

Build firmware abstractions so you can migrate within a vendor family without refactoring the entire driver stack.

Concrete Tips for Robust Cortex‑M Firmware

- Use the MPU early, even in debug builds. Protect stacks and set guard regions to catch overflows.

- Keep ISRs tiny. Defer work to tasks using queues/semaphores. Never block in an ISR.

- Exploit DMA. Move repetitive I/O and sampling off the CPU. Double‑buffer for continuous streaming.

- Place hot code/data wisely. ITCM/DTCM or low-latency SRAM for control loops; Flash/QSPI for cold paths.

- Profile with DWT. Count cycles around drivers and algorithms; optimize only what’s hot.

- Use tickless idle in RTOS apps. Let the MCU sleep between timers rather than waking at a fixed 1 kHz tick if not needed.

- Calibrate clocks and ADC references. Many low‑power families benefit from runtime trim for accuracy.

- Plan for OTA from day one. Partition Flash (or QSPI) for A/B images; reserve a small, verified bootloader.

- Harden interfaces. Use CRC for packets, watchdogs per subsystem, and brown‑out detection tuned to your regulator’s behavior.

Real-World Patterns and Case Studies

- Battery asset tracker: An STM32L4 (M4F) samples GNSS intermittently, uses a low‑power LTE‑M/NB‑IoT modem in short bursts, and logs data to QSPI. By offloading sensor sampling to DMA and sleeping between fix windows, it hits multi‑month life on a small Li‑ion.

- Industrial gateway: An STM32H7 (M7) runs Ethernet, TLS, and a Modbus/TCP stack while sampling multiple ADC channels via DFSDM. Critical control loops run from ITCM; network stacks execute from cached Flash. MPU isolates third‑party plugins.

- Audio processing: An NXP i.MX RT1062 (M7 at 600 MHz) performs 32‑band EQ and reverb on stereo audio at 48 kHz with sub‑10 ms latency, using SAI + DMA and TCM for the inner loops. External QSPI holds impulse responses.

- BLE wearable: Nordic nRF52840 (M4F) performs sensor fusion (gyro+accel+mag) at 100 Hz with CMSIS‑DSP, BLE notifications every 20–50 ms, and sleeps between intervals. A 225 mAh cell yields many days of continuous use.

These are not edge cases—they’re representative of what modern Cortex‑M systems can do affordably.

How Cortex‑M Shapes Team Workflow

- Standardized startup: CMSIS packs and vendor projects give a “known good” clock tree and linker script out of the box.

- Repeatable debug: Every engineer can attach a J‑Link or ST‑Link, set a hardware breakpoint, and log via ITM in minutes.

- Shared artifacts: Middleware ports and examples are widely available, so your “first UART with DMA” or “USB CDC device” is hours, not days.

- Measurable performance: DWT cycle counts and ETM traces anchor discussions around facts, not hunches.

Teams ship faster not only because the chips are fast, but because the friction is low.

Pitfalls to Avoid (Even Pros Step In These)

- Flash wait states ignored: At higher clocks, unbuffered Flash stalls can blow real‑time budgets. Use caches/TCM for hot code.

- Priority inversions: Misusing NVIC priority bits or mixing RTOS priorities with ISR priorities can create jitter or deadlocks. Define a clear priority map.

- Overusing HAL in hot paths: HAL makes bring‑up fast, but its abstraction cost can be high inside 20 kHz ISRs. Transition critical paths to LL or direct registers after prototypes work.

- Unaligned buffers for DMA: Many DMA engines require word alignment; misaligned buffers cause silent data corruption or faults.

- Power domain assumptions: Not all peripherals run in deep sleep. Read the reference manual’s sleep compatibility tables.

A day spent profiling and reading the memory/peripheral “gotchas” chapter saves weeks later.

The Road Ahead: Helium, Secure by Default, and Smarter Edges

Trends to watch that will further amplify Cortex‑M’s role:

- Vector math everywhere: M55 + Helium broadens what’s feasible in audio, sensing, and ML without separate DSPs. Library support is maturing quickly.

- NPUs at MCU scale: Ethos‑U55/U65 paired with M33/M55 offload convolutions and activation functions, cutting inference energy by orders of magnitude for certain models.

- Security as a building block: TrustZone‑M and TF‑M are becoming default baselines, not optional add‑ons. Expect more devices with secure boots, on‑die key storage, and side‑channel hardened crypto.

- Ecosystem consolidation: Zephyr’s momentum as a vendor‑neutral RTOS and the growth of CMSIS‑Pack tooling mean more reusable code across vendors.

- C++ and Rust in MCUs: Better compilers and zero‑cost abstractions encourage safer code without sacrificing performance; expect stronger Rust HALs and RTIC‑style frameworks.

The arrow points toward richer features at MCU power budgets, not toward moving everything to application processors.

Cortex‑M didn’t just upgrade the instruction set; it standardized a development experience. With consistent real‑time behavior, a deep ecosystem, and silicon choices from sub‑dollar to powerhouse M7/M55 designs, it gives embedded teams a platform to build ambitious products quickly. If your last MCU project felt like a wrestling match, your next one—with the right Cortex‑M, tooling, and design habits—can feel like engineering again.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts