Five Brain Myths About Depression You Still Believe

9 min read Debunk key brain myths about depression with science-based insights that change how we understand this mental health challenge. (0 Reviews)

Five Brain Myths About Depression You Still Believe

Depression is often described as a disorder of the brain, yet it is also clouded by countless myths and misunderstandings. Despite remarkable advances in neuroscience, outdated ideas about depression’s nature persist—not only among the public but sometimes even among well-meaning clinicians and policymakers. These myths can leave sufferers feeling blamed, isolated, or misunderstood, and they make it harder to access effective treatment. Let’s critically examine five pervasive brain myths about depression and replace them with science-backed realities.

Myth 1: Depression Is Just a Chemical Imbalance in the Brain

Perhaps the most entrenched oversimplification is that depression stems solely from a "chemical imbalance," specifically of serotonin in the brain. This myth originated partly from the early success of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), medications that increase serotonin levels and relieve depressive symptoms in many patients.

However, modern research paints a more complex picture. The brain is a highly plastic organ, and depression involves structural and functional changes in numerous regions—like the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala—not just neurotransmitter fluctuations. Additionally, neuroinflammation and alterations in brain connectivity contribute significantly. Researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health emphasize that "the chemical imbalance hypothesis is too simplistic and should not be the sole explanation for depression."

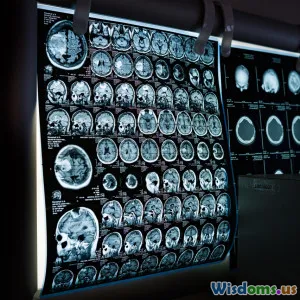

For example, studies using brain imaging show reduced hippocampal volume in people with chronic depression, suggesting that stress-related neurotoxicity or reduced neurogenesis contributes beyond neurotransmitter levels.

Takeaway: Viewing depression as only a chemical imbalance trivializes its complexity and may inhibit patients from seeking broader therapies like psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, or neuroplasticity-focused treatments.

Myth 2: Depression Is a Brain Disease Like Alzheimer's

It is easy to lump depression with neurological diseases because it involves brain changes, but depression is fundamentally different from neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. Those diseases involve irreversible loss of neurons and function, while depression is often characterized by reversible changes in brain activity and plasticity.

Functional MRI studies have revealed that many brain areas implicated in depression can normalize with effective treatment. For example, symptoms improve following cognitive-behavioral therapy, antidepressants, or physical exercise, which stimulate neural circuits’ reorganization. Unlike irreversible brain diseases, this malleability mirrors depression’s episodic nature.

Yet, framing depression as a "brain disease" causes public confusion about prognosis and stigma. Psychiatrist Dr. Helen Mayberg, known for groundbreaking brain-stimulation treatments for depression, states, "Depression is not neurological death—it’s a functional disorder of circuitry."

Example: Patients completing an 8-week mindfulness program show increased connectivity in prefrontal regions correlated with symptom relief, despite no pharmacologic intervention.

Myth 3: People with Depression Have "Broken" Brains

Another harmful myth is that depression permanently "breaks" a person’s brain. This misconception fosters stigmatization, making individuals feel they are fundamentally flawed or permanently damaged.

In reality, many of the brain changes linked to depression represent adaptive or maladaptive responses to stress and trauma. Brain plasticity—the organ’s ability to reorganize—means that these changes can often be reversed or mitigated through treatment, lifestyle shifts, and social support.

The emergence of treatments like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and ketamine therapy leverages this plasticity, encouraging new neural connections rather than repairing a "broken" brain.

For instance, a global meta-analysis pooling neuroimaging from over 1,500 patients revealed patterns consistent with reversible alterations rather than permanent injury.

Holder of the Stanley Foundation endowed chair at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Francis McMahon, emphasizes, "We should move away from thinking of depression as brain damage and instead as a disruption that can be repaired."

Myth 4: Depression Only Affects Emotion Centers of the Brain

Many presume depression mainly disrupts emotion-related brain areas. While limbic structures like the amygdala and hippocampus are indeed involved, the reality is far more intricate.

Depression impacts broad brain networks, including those governing executive functioning, decision-making, motivation, and attention. The default mode network (DMN)—a brain system active during self-referential thoughts—shows abnormal activity in depression, explaining phenomena such as rumination and negative self-talk.

Moreover, diminished activity in the prefrontal cortex can impair cognitive control over emotions.

A striking example comes from imaging studies where patients performing problem-solving tasks revealed decreased engagement of frontal networks, correlating with the difficulty many experience concentrating or making decisions during depressive episodes.

Recognizing this broad network dysfunction can help clinicians tailor treatments better; for example, cognitive remediation therapy targets these executive deficits, supplementing mood-focused treatments.

Myth 5: Depression Is Only a Brain Problem; Environment Doesn’t Matter

Perhaps the oldest myth is that depression resides solely within the brain, ignoring crucial environmental and social factors.

Risk factors such as prolonged stress, childhood trauma, isolation, socioeconomic hardships, and adverse life events profoundly impact brain function and depressive risk. Epigenetic studies demonstrate how environmental exposures can alter gene expression relevant to brain circuits involved in mood regulation.

The landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study revealed that high ACE scores strongly predict adult depression, highlighting the inseparability of environment and brain.

A neuroscientist Dr. Bruce McEwen coined the term "allostatic load" to describe how chronic stress overloads bodily and brain systems, leading to depression vulnerability. This underscores that mental illness is often an interaction between biology and environment.

Practical implication: Effective mental health care requires addressing social determinants, not just biochemistry. Psychosocial interventions, community support, and policy changes are critical alongside medication and therapy.

Conclusion

Depression is a multifaceted, complex mental health condition that cannot be pigeonholed into simplistic brain-only models. Debunking these five pervasive myths helps us foster empathy, reduce stigma, and embrace holistic, evidence-based approaches.

Understanding that depression is more than just a chemical imbalance, recognizing its reversible neural dynamics, appreciating diverse brain network involvement, and acknowledging the powerful role of environment all empower better care. If you or someone you love struggles with depression, remember: the brain is adaptable, and recovery is possible with comprehensive, compassionate support.

Embrace science over myth, and let knowledge inspire hope.

References

- Harmer, C. J. et al., "Why we need new models of depression," Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2021.

- National Institute of Mental Health, "The Science Behind Mental Health Staffing," 2022.

- McEwen, B. S., "Stress and the Brain: Pathways to Depression," Neuropsychopharmacology, 2019.

- Mayberg, H. S., "Defining the Neural Circuitry of Depression," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 2020.

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, CDC, 2019.

- Dunlop, B. W., Mayberg, H. S., "Neuroimaging and Treatment of Depression," Neurotherapeutics, 2014.

This article aims to educate readers with accurate neuropsychiatric knowledge and to inspire action toward deeper understanding and comprehensive recovery from depression.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts