Writing instructions for complex systems without confusing your team

31 min read Practical framework to write clear, unambiguous instructions for complex systems, with examples, templates, and testing techniques to reduce errors, speed onboarding, and align cross-functional teams. (0 Reviews)

Writing Instructions for Complex Systems Without Confusing Your Team

Complex systems are everywhere: distributed architectures, multi-step sales motions, regulatory compliance workflows, cross-cloud deployments, even content production pipelines. They’re powerful precisely because many moving parts coordinate to get valuable work done. But when it’s time to write instructions for those systems, complexity becomes a trap. A vague checklist or a poorly structured runbook is worse than none at all—people follow it with confidence right up until they don’t, and your team pays with downtime, rework, and stress.

This article shows how to craft instructions that your team can trust under pressure. It blends practical patterns, examples, and a repeatable “clarity audit” you can use in fifteen minutes. Whether you lead an SRE team, a product marketing org, or a regulated biotech lab, the core mechanics of writing for complex systems are the same: reduce cognitive load, make decisions explicit, and embed verification so people know they’re still on the rails.

Along the way, you’ll see concrete examples—a messy deployment guide turned into a crisp runbook, guardrails for branching logic, and rollback recipes. We’ll focus on formats that work (how-to, playbooks, SOPs), language patterns that survive stress, and the organizational habits that keep instructions alive instead of stale.

What Makes Instructions Confusing in Complex Systems

Let’s start with the failure modes. The following patterns show up again and again when teams struggle:

- Ambiguity in actors: Instructions don’t say who should do what. “Restart the service” begs the question: who has access? Who has permission to restart production?

- Missing preconditions: Steps assume a state that doesn’t exist (e.g., “deploy the chart” without the repo added, credentials configured, or feature flags created).

- Hidden decisions: Branches are buried in prose (“If this is a minor update… otherwise…”), so readers miss forks or don’t know which path they’re on.

- Overloaded steps: Single steps combine several actions and checks, making it hard to verify progress or parallelize work.

- Documentation drift: The system evolved, but the doc didn’t. The instructions reference dashboards that no longer exist or names from a prior reorg.

- Context switches: Steps force readers to jump across tools, dashboards, and jargon, burning working memory on switching rather than doing.

Cognitively, humans can juggle only a few chunks of information at once. Complex systems push beyond that limit. Good instructions fight this by chunking, naming states, and embedding verification points. Great instructions do one more thing: they make success look obvious through observable outcomes (“you should see X events per minute in Topic Y” rather than “make sure it worked”).

Diagnose the Complexity: Map the System and the Work

Before you write, take 30–45 minutes to map both the system and the task. You’re not making a full architecture diagram; you’re creating a writer’s map—just enough to spot where instructions will need clarity.

- Identify components and their boundaries: For a microservices deploy, this might be image registry, CI pipeline, Kubernetes cluster, service mesh, feature flag service, monitoring stack.

- Name external dependencies: Identity provider, payment gateway, external data feeds, or legal approvals.

- Trace the “work path”: From trigger to outcome. Example: developer merges code -> CI builds -> image pushes -> staging deploy -> tests -> manual approval -> production deploy -> traffic shift -> verify metrics -> announce release.

- Mark decision points: Canary pass/fail thresholds, manual approvals, rollback criteria, compliance sign-offs.

- Note failure surfaces: Rate limiting, flaky tests, secrets rotation, cross-region replication lag.

A simple whiteboard sketch or a one-page diagram is enough to reveal where ambiguity would creep in. If you can’t map the workflow, you can’t write instructions for it—clarity in writing starts with clarity of the work.

Define the Reader: Roles, Preconditions, and Decision Rights

A frequent source of confusion is writing for “everyone.” Define who can successfully execute the instructions and under what conditions.

- Role clarity: “Primary audience: On-call SREs with production access. Secondary audience: Developers shadowing.”

- Preconditions and access: “Requires kubectl access to prod cluster, role X in IAM, and VPN.”

- Decision rights: “The on-call engineer may rollback without approval if SLO breach > 5 minutes. For canary fails below this threshold, consult the incident commander.”

- Skill assumptions: “Assumes comfort with Kubernetes basics (pods, services, logs). Does not assume PromQL expertise.”

Write these at the top of the runbook or SOP. The more explicit you are, the fewer Slack pings you’ll get at 2 AM.

Choose the Right Document Type: Runbook vs. SOP vs. Playbook vs. Knowledge Article

Not all instructions serve the same purpose. Pick the right format to match the risk, frequency, and variability of the task.

- Runbook: Step-by-step operational guide for a specific task with known paths (e.g., “Deploy the Payments service to production”). Great under time pressure. Includes verification and rollback.

- SOP (Standard Operating Procedure): Formal, auditable process often used in regulated environments (e.g., “Validate batch release for GMP compliance”). Includes versioning, sign-offs, and training requirements.

- Playbook: Decision-oriented guide for variable scenarios (e.g., “Respond to a latency incident”). Emphasizes branching logic, diagnostics, and escalation.

- Knowledge Article: Conceptual info or how-to for reusable knowledge (“How feature flags work in our stack”). Good for learning and context, not for in-the-moment execution.

Mislabeling causes mis-expectations. A “playbook” that’s secretly an SOP will frustrate readers who need a straight path, not a tree.

Structure That Scales: The 7-Layer Instruction Pattern

Use a consistent scaffold so your team knows where to find what they need:

- Purpose and outcomes

- State what the task accomplishes and the observable outcome. “Roll out v2.3 of Payments to 100% of traffic with zero downtime. Success = no error-rate regression > 0.2% for 15 minutes after full rollout.”

- Preconditions

- Access, environment, time windows, and prerequisites. “Maintenance window: 30 minutes. Requires prod access, PagerDuty active. CI pipeline green.”

- Inputs and outputs

- Inputs: artifact versions, ticket IDs, environment variables. Outputs: updated dashboard links, confirmation notes, audit artifacts.

- Golden path steps

- The main, linear sequence for the common case.

- Decision points and branches

- Clear conditions for branching, with guardrails and links to branch-specific steps.

- Exception handling and rollback

- What to do when things don’t go to plan, including who to call and how to revert safely.

- Verification and closeout

- What “good” looks like, how to verify it, and what to document/announce.

This pattern compresses complexity into predictable sections. When your team recognizes the shape, they move faster with less anxiety.

Write Steps That Survive Stress: Action-Oriented Micro-steps

In high-stakes tasks, small mistakes compound. Steps should be easy to scan and execute.

- Imperative verbs: Start steps with a strong verb and an object. “Apply the Helm chart with values-prod.yaml.” Avoid “we should” and “try to.”

- One action per step: If you must chain, break into lettered sub-steps (a, b, c). This enables “call and response” during pair execution.

- Include where and how: “In the prod shell, run: kubectl -n payments get pods. Expect to see pods with image tag 2.3.0.”

- Annotate expected states: “You should see 3/3 pods Ready within 5 minutes.”

- Keep steps short: If a step requires >2 minutes or multiple screens, it’s likely two steps.

Example micro-step rewrite:

Before:

Deploy the new version and check that it’s running correctly.

After:

1. In the prod shell, set the release version: export VERSION=2.3.0.

2. Deploy: helm upgrade payments ./chart -f values-prod.yaml --set image.tag=$VERSION.

3. Verify rollout: kubectl -n payments rollout status deploy/payments --timeout=5m.

4. Confirm pods on new version: kubectl -n payments get pods -o wide | grep $VERSION.

Each action is specific and verifiable, reducing back-and-forth.

Make Decisions Explicit: Branches, Guards, and Gates

Branches are where instructions most often fail. Make them unmissable and tied to measurable conditions.

- Guards: Preconditions that must be true before entering a path. “Proceed to canary only if error rate < 0.5% for 10 minutes.”

- Gates: Positive confirmations or approvals required to continue. “Security sign-off ticket APPROVED.”

- Branch naming: Name branches like functions. “Path A: Canary passes,” “Path B: Canary fails.”

- Visual anchors: Even if you don’t include a diagram, signal branches with clear headings and bullet markers.

Branch snippet:

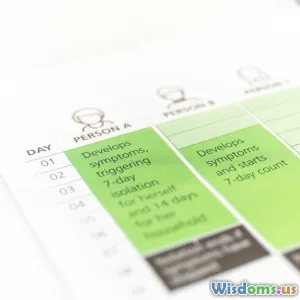

Decision: Canary error rate within 0.5% of baseline for 10 minutes?

- If YES, go to Path A: Increase to 50% traffic.

- If NO, go to Path B: Hold canary and diagnose (logs, SLOs, feature flags).

When branching criteria are specific, on-call engineers make the right call without second-guessing.

Embed Observability: Where to Look and What “Good” Looks Like

Nothing reduces confusion like clear observables. For each verification step, answer three questions:

- Where to look: “Open Grafana dashboard ‘Payments/Service Health’.” Include direct URLs where possible.

- What the metric is: “Error rate (5xx) per minute.”

- What good and bad look like: “Good: 0.1%–0.3% for 10 minutes post rollout. Bad: sustained >0.5% or spikes aligned with traffic ramp.”

Write verification steps as if a new team member is following them. Remove insider shorthand like “check logs.” Instead: “In Kibana, filter by service:payments AND env:prod, then search for ‘timeout’ in the last 5 minutes. Expect fewer than 3 entries.”

Reduce Cognitive Load with Chunking and Visual Anchors

Chunking creates “breathing spaces” for the brain. Techniques:

- Segment by goal: Group steps into blocks that produce a specific outcome (e.g., “Prepare,” “Deploy,” “Verify,” “Rollback”).

- Add brief “why” statements: One-line rationale per block.

- Use bullets and numbered lists: Favor structure over prose.

- Keep line length short: 60–80 characters improves scanning.

- Use consistent callouts: “Note,” “Caution,” “Tip.” Don’t invent new callout styles for each doc.

Example block chunking:

Prepare (why: ensure safe rollout)

- Freeze unrelated deployments in #deployments channel.

- Confirm CI green for payments@main.

- Announce planned release and rollback plan in #payments.

Readers recognize the rhythm: prepare, execute, verify.

Example: Turning a Messy Deployment Guide into a Clear Runbook

Consider this realistic “before” excerpt:

Before:

Deploy payments by pushing the new image. Make sure everything is green. If there are errors, revert. Don’t forget to tell people in Slack.

This is ambiguous everywhere: where to push, how to check, what “green” is, how to revert, who to tell.

After (runbook excerpt):

Title: Payments v2.3 Production Rollout

Audience: On-call SRE (prod access)

Purpose: Roll out v2.3 with zero downtime; success = error rate unchanged (<0.3%) for 15 mins post full rollout.

Preconditions:

- CI pipeline green for payments@v2.3 tags.

- On-call has kubectl prod access and PagerDuty active.

- Maintenance window approved in #releases.

Golden Path

1. Announce start: Post "Starting Payments v2.3 rollout (runbook link). Golden path; rollback if error rate >0.5% for 5 mins." in #releases and #payments.

2. Set the version: export VERSION=2.3.0

3. Deploy canary (10% traffic): helm upgrade payments ./chart -f values-prod.yaml --set image.tag=$VERSION --set canary=10

4. Verify canary (10 mins):

- Dashboard: Grafana -> Payments/Service Health -> error rate (5xx/min).

- Good: 0.1%–0.3% steady. Bad: >0.5% sustained 2+ mins.

5. Decision: If error rate within 0.5% of baseline for 10 mins, go to Path A; else go to Path B.

Path A: Increase traffic to 50%

6. Update traffic split: flagctl set payments_traffic_split 50

7. Verify metrics (5 mins): same dashboard; lat p95 within 10% of baseline.

8. If stable, increase to 100%: flagctl set payments_traffic_split 100

9. Verify full rollout (15 mins): error rate <0.3%; p95 latency within 10% of baseline.

10. Closeout: Announce success with Grafana screenshot in #releases; update CHANGELOG.

Path B: Canary Issues

B1. Freeze traffic at 10%; post "Canary holding at 10% due to error rate >0.5%" in #payments.

B2. Inspect logs: Kibana query service:payments env:prod message:timeout (5m window). Expect <3 events; if >3, proceed to rollback.

B3. Rollback: helm rollback payments --to-revision PREV

B4. Verify rollback: error rate returns to baseline within 5 mins.

B5. Notify incident commander if error rate remains >0.5% after rollback.

Notice how each piece provides location, action, and verification. It’s not verbose; it’s exact.

The Golden Path and Off-Ramps

A golden path is the simplest, most common successful route. Treat it as the highway. Off-ramps are branch paths for when reality diverges.

- Keep the golden path linear: Don’t interleave troubleshooting in the middle. Instead, insert a clear decision point with links to off-ramps.

- Limit off-ramps: Too many branches indicate the need for separate runbooks or modular guides.

- Make re-entry clear: When off-ramps resolve, show exactly where to rejoin the golden path.

Signal off-ramps in your headings or with markers like “Path B: Canary Issues” so scanning readers don’t miss the turn.

Error Handling and Rollback Recipes

Your instructions are only as good as your worst day. Build in recovery.

- Define rollback triggers numerically: “If error rate >0.5% for 5 consecutive minutes or 3 spikes >1% within 10 minutes, rollback.” Avoid subjective “seems high.”

- Precompute rollback steps: Don’t invent them under pressure. Test them quarterly.

- Include blast radius notes: What side-effects rollback causes (schema versions, cache data, analytics events).

- Shorten search: Provide direct commands and links. “helm rollback payments --to-revision PREV” plus the command to find PREV quickly.

- Post-rollback protocol: Who to inform, what to log, where to file RCA seeds.

Example rollback recipe snippet:

Trigger: error rate sustained >0.5% for 5 mins OR p95 latency >2x baseline for 3 mins.

Steps:

1) Freeze traffic split: flagctl set payments_traffic_split 0 (route to prior stable release).

2) Rollback helm release to PREV: helm history payments | head -n 2; helm rollback payments <revision>.

3) Validate: Grafana -> Payments/Service Health returns to baseline within 5 mins.

4) Announce rollback completion in #releases with screenshot.

5) Create incident with tag "payments-rollback" for follow-up RCA.

Cross-Functional Dependencies: Hand-offs Without Drop-offs

Complex systems usually cross team boundaries. Hand-offs are notorious failure points.

- Define interfaces: “SRE hands off to Data Engineering after step 7 when Kafka lag is stable <100 messages for 10 mins.”

- Time expectations: “Security review SLA is 24 hours; do not proceed without approval.”

- Shared artifacts: Clearly name tickets, forms, or dashboards used by multiple teams.

- Escalation ladders: Provide a primary and backup contact, not just a channel name.

A good hand-off reads like a relay baton pass: clear, predictable, and with momentum.

Keep It Live: Versioning, Ownership, and Review Cadence

Dead docs kill trust. Treat instructions like code.

- Docs-as-code: Store runbooks in the same repo as the service, versioned with changes.

- Ownership: A named owner (team, role) is responsible for updates. Avoid “everyone’s job.”

- Review cadence: Set a quarterly or release-based review. Stamp the doc with a “Last verified” date.

- Change triggers: Every change to scripts, dashboards, or configs must include a doc update in the PR checklist.

- Deprecation policy: When a runbook is superseded, clearly mark it and link to the new one. Don’t delete until you migrate links.

A simple fact: teams trust what is fresh. Even adding a “Last verified on 2025-06-15 (by Alex R.)” banner increases usage because readers believe it’s not stale.

Tooling: Lightweight Formats and Automation Hooks

Choose tools that make doing the right thing easy.

- Markdown with front matter: Keep it simple, searchable, reviewable. Add metadata for audience, preconditions, and verification.

- Snippet reuse: Centralize repeated blocks (e.g., standard canary verify steps) to avoid drift.

- Command blocks with copy buttons: Reduce typos. Where possible, parameterize with environment variables.

- Automation hooks: Link steps to scripts or ChatOps commands. Example: a slash command to generate canary dashboards or post release announcements.

- Templates: Provide runbook templates using the 7-layer pattern.

Example front matter:

---

title: Payments v2.3 Rollout

owner: sre-payments

audience: on-call-sre

last_verified: 2025-06-15

preconditions:

- prod kubectl access

- PagerDuty on-call active

- maintenance window approved

---

Templates and light automation make “good documentation” the path of least resistance.

Testing Instructions: Dry Runs, Fire Drills, and Shadowing

You wouldn’t ship code without tests. Don’t ship instructions without them.

- Dry runs in staging: Run the full guide end-to-end in a realistic environment at least once per quarter.

- Fire drills: Simulate incidents and execute playbooks. Measure time to execute, decision clarity, and error rates.

- Shadowing: Have a newcomer perform the steps while a veteran observes silently. Any question they ask is a doc improvement.

- Debrief: After drills, capture friction points and update docs within 48 hours.

A useful metric here is Time to First Success (TTFS) for a new team member running the doc. If TTFS is high, your instructions need work.

Language and Tone: Precision Without Pedantry

Language shapes cognition. Choose words that guide action.

- Favor the imperative: “Run,” “Verify,” “Escalate.”

- Ban ambiguous pronouns: Replace “it” with concrete nouns (“the payments deployment”).

- Use parallel structure: Keep the same phrasing pattern across steps to reduce reading overhead.

- Define terms once: If you must use internal jargon, define it briefly at first use.

- Keep sentences short: Aim for 12–18 words; long sentences hide decisions.

Bad: “It might be necessary to quickly check it’s okay before continuing.”

Better: “Verify error rate <0.3% for 5 minutes before proceeding.”

This is not about dumbing down. It’s about making the next action inescapably clear.

Accessibility and Inclusivity: Designing for Diverse Teams

Clarity is inclusive.

- Screen reader-friendly headings and lists: Use semantic headings, ordered steps, and descriptive link text.

- Don’t rely solely on color: When referencing dashboards, describe thresholds and patterns, not just colors.

- Avoid tiny screenshots: Prefer text-based instructions and copyable commands. If you include images, add alt text and annotations.

- Time zones and locales: For scheduled tasks, specify time zones (UTC) and date formats (YYYY-MM-DD).

- Language inclusivity: Avoid idioms and culturally specific references that confuse non-native speakers.

Designing for everyone reduces errors for everyone.

Metrics: Measuring Clarity and Impact

You can measure documentation quality indirectly through outcomes.

- Execution time variance: Lower variance suggests clearer steps.

- Support pings per execution: Fewer questions mean better docs.

- First-pass success rate: Percentage of runs completed without rollback.

- Mean Time to Decision (MTTD): Time from encountering a branch to choosing a path.

- Doc freshness: Percentage of critical runbooks verified in the last 90 days.

Set targets. For example: “Reduce support pings during deployments by 50% in two quarters.” Tie doc updates to observable reductions in friction.

Checklist: The 15-Minute Clarity Audit

Use this quick audit to improve any complex-system instruction set.

- Purpose: Is the desired outcome explicit and measurable?

- Audience: Does it name the primary reader, preconditions, and decision rights?

- Structure: Does it follow a consistent pattern (purpose, preconditions, inputs, steps, decisions, exceptions, verification)?

- Steps: Are steps imperative, specific, and verifiable? One action per step?

- Decisions: Are branching criteria measurable and unmissable?

- Observability: Does each verification step name where to look and what good/bad look like?

- Rollback: Are rollback triggers numeric with tested steps and expected results?

- Hand-offs: Are hand-offs to other teams explicit with SLAs and contacts?

- Freshness: Is there a last-verified date and owner? Any stale links?

- Accessibility: Are instructions usable without images and color cues? Copyable commands included?

- Tooling: Are scripts and dashboards linked directly? Any automation hooks?

- Test coverage: Has the doc undergone a dry run or fire drill in the last quarter?

- Brevity: Are there unnecessary explanations that belong in a knowledge article instead?

- Consistency: Are names (services, flags, dashboards) consistent throughout?

- Closeout: Does the doc explain how to confirm success and communicate completion?

Spend 15 minutes, fix three issues, and you’ll often cut execution time by a third.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Mixing concepts and execution: Keep conceptual background out of runbooks; link to knowledge articles instead.

- “We’ll remember”: Relying on tribal knowledge creates brittle execution. If it matters, write it.

- Screenshots as steps: UI changes break screenshots; prefer text and selectors. If a screenshot is necessary, include a timestamp and describe the target elements.

- Everything in one doc: Split massive documents. A 1,000-line runbook is 990 lines too long. Use modular docs and link.

- Silent changes: If a script or flag changes behavior, update docs in the same PR and tag owners.

- Over-optimizing for one incident: Don’t let a single odd event clog your golden path. Handle rare cases in off-ramps or separate playbooks.

Avoiding these traps maintains clarity at scale.

Final Thoughts: Make Clarity a Team Habit

Complex systems won’t get simpler on their own. The way your team writes—and rewrites—instructions is a controllable lever for reliability, speed, and confidence. Treat instructions as operational code: design them with a robust structure, test them regularly, and measure their impact. Keep the golden path short and explicit, push complexity into off-ramps, and make decisions measurable and visible.

Most of all, make clarity a habit. Bake a 15-minute clarity audit into release checklists. Pair on high-stakes runbooks like you pair on critical code. Celebrate clean instructions in retros. When your team can execute confidently at 2 AM, it’s not luck—it’s the compounding return on disciplined, reader-centered writing.

Rate the Post

User Reviews

Popular Posts